For guys like me, the fact that an auteur genius like Hitchcock would turn out to be enough of a fanboy of the prototypical alien invasion story gives the old Hollywood legend this strange sense of humanity that goes a long way toward making him seem less aloof, cool, and detached as his now famous public persona. It suggests the image of this young kid growing up on the outskirts of London, and rather than a pint-sized version of the dapper, sadistic Master of Suspense, he's like this walking cliche of geekdom. The sort of kid you might expect to find making his way home from school in suspenders, with maybe a bottle of soda pop in one hand, and either a newspaper comic, a dime novel purchased off a drugstore rack, or maybe the latest issue of The Strand Magazine tucked under one arm, hoping against hope that Arthur Conan Doyle might have found his way back to Baker Street one more time.

The information provided by Warren allows us to imagine a further variation on this image. Instead of an Across-the-Pond equivalent of a Pulp Crime serial, its one of those early periodicals that were making their first tentative stabs at Interplanetary fiction, just before the advent of Hugo Gernsback's Amazing Stories helped launch the genre's much touted Golden Age. The picture of a young nerd immersing himself in the Fantastic genres is as cliche, and dime a dozen as they come. Nor was it anything like an isolated incident even back then. The proverbial woods, as the saying goes, was and is still "full of 'em". What comes as a shocker is to find out that a guy like Hitchcock counts as one of the tribe. In retrospect, I guess that knowledge shouldn't come as too great a surprise. Hitch would never have been the artist he became if didn't have an understanding and sympathy for the popular forms of storytelling. I think it's just the way he presented himself in public, and the style he infused into his best work always manages to give off this sense of class, and taste. He makes you feel as if you're watching a type of cinema for sophisticates. Realizing he was a Sci-Fi nerd is a left field surprise.What Warren's information tells the astute reader, more than anything, is just how much of an impact H.G. Well's Martian novel has left on artists and fans throughout the world.The best way to describe a phenomenon like that is to label it a template setter. It's the sort of thing that, like Mt. Everest, just happens every now and again. Some artist comes along, and either by the purest dumb luck, a burst genius, or most likely a combination of the two results in one of those stories that manages to burrow its way into the unconscious zeitgeist of the culture at large. This seems to have been the fate of Wells's space yarn, and it's shelf life in the public consciousness appears to be guaranteed for quite some time.

It appears to have left enough of an impact on the mind of someone like a young Hitchcock to such an extent that the man who would later leave a definitive stamp on the Mystery genre still felt compelled to hunt down one of the main shapers of Speculative Fiction all the way in Nice (ibid), and try to ask his permission to make a movie out of it. It's one of those great what-if moment that history like to tease us with. Because: reasons. It means at one point, we could have had an early, big screen, Invaders from Mars epic from the same director who brought you Psycho, and quite possibly featuring Orson Welles himself in the starring role. None of that ever happened. And it's at moments like these when it's possible to understand how people keep asking the question: Why can't we have nice things?

Wells doesn't seem to have shown any reluctance to Hitchcock's film proposal. The one monkey in the wrench, as Wells pointed out, was that the rights for the novel were then locked up with Paramount studios, and Hitchcock was still a young novice at the time. His star was rising, yet even though his career would soon be on the make, it was still at that point were he was considered "Little People" by the moguls running Hollywood at the time. That's got to be one of the sharpest kicks in the teeth history had in store. What makes it worse is that it was lying in wait for such a long time, and still you never see it coming. So, the movie rights to the book languished away, possibly in some studio vault, way out there in the Paramount lot in Hollywood. There the rights to the novel sat, and waited, with all the time in the world, and nothing to do. Hitchcock became a film legend, and still no one bothered with the property. H.G. Wells himself, the man who first brought Mars down to earth, shuffled off whatever we think these mortal coils are supposed to be, and the rights to his work stayed right where the were. A carbon copy paper version of the Sphinx, and just as inscrutable. Nothing important happened with them for the longest time. And then Hungarian producer George Pal took them up.

The Basic Idea, and It's Context.

I think it's safe enough to assume most people still have this vague sort of familiarity with the concept. At least they do for the moment, anyway. One of the most interesting things about Wells's original idea is the tenacity with which its managed to stick around in the collective memory of the audience across three centuries, and several generations. Apparently there's just something about the idea of the invasion from outer space that is able to carve a permanent sort of groove in the popular consciousness. It's one of those ideas that is automatically big enough to catch on, no matter where you happen to be on the globe, or at any given point on the timeline. All it amounts too is an ongoing testament to Wells's skill as an author. He was lucky enough to unearth an archetype, one that is potent enough to speak to the collective nightmares of readers and viewers across all possible barriers. In that sense, Wells could be said to have discovered a kind of trans-generational language, one that doesn't need much in terms of translation in order to do its job well. So that means a film adaptation is a guaranteed cinch, right?Let's take things one at a time, starting with the most basic of plot summaries. Everybody at this moment in time still has a sort of rough working knowledge of Wells's plot. It involves a capsule, or spaceship coming down to Earth from the planet Mars. It's the first vanguard of an alien military force. They've come from another world conquer our own. What follows can best be described as a very hostile form of first contact. It also might just be the most iconic moment in the entire story. A group of earthlings delegates themselves as an impromptu, interplanetary welcoming committee. Three of them group together and approach the crashed Martian cylinder, waving a white flag. Their intentions seem honest enough, and so do the new visitors. Each species presents an object toward the other. All the Martians decide to offer is a blast from their heat ray, a weapon which disintegrates or else incinerates its chosen target in a manner of seconds. This is the first galactic handshake exchange that Wells treats his readers to. It also remains as a potent symbol for what is apparently a lingering fear in the minds of a great deal of people, even in the 21st century. This in turn may be a good explanation for the story's staying power. From their, the reader is treated to a quasi-documentary account of how the Martians begin to lay waste to the human species, and the near extinction of mankind.

In the end, it is not the might of Earth's combined fire powers, yet rather one of the lowliest of bacterial organisms, an obstacle to which man has had aeons to adjust himself to, which brings the Martians first to their knees, and then to their ultimate defeat and downfall. Hence, the small, green planet lives to fight for another day, and from now on, to always keep watching the skies. This is the content of Wells's story in its most basic outline, and it tends to be the blueprint that every other adaptation (whether literal or "in spirit") builds from, or else riffs off of. There appears to be this built-in sense of durability to the concept Wells hit upon. It can work fine on its own (in the right hands), and yet it can also act as an artistic springboard that allows the next artist to branch the concept off into a lot of other forms of the same idea, while also still finding ways of creating an aesthetic identity of its own. That's how you go from The War of the World to an Invasion of the Body Snatchers, or The Thing From Another World, and from there all the way to Ridely Scott's Alien (1979). I have called Wells's original idea an archetype. All those titles and riffs listed above stand as the best possible proof of the idea, and its staying power.As I've noted at the beginning, the creative potential of Wells's novel for the big screen was not lost on on the filmmakers of the time. Even as the then new medium of film was starting to come into its own, directors and writers had an awareness of the Martian book, and were turning the cinematic possibilities of the story over in their minds. Bill Warren even gives us the contents of a 1925 pitch outline for one of the earliest, unrealized versions of the invasion story (876-78). It's set in America at the turn of the century, and based on how Warren describes it, it's easy to agree with him that we're all better off for its never having been made. Imagine some of the worst stereotypes available in that era, and then plastered all over the screen as melodrama, and you begin to have an idea of why some things are better left on the cutting room floor. Like I've said, the script rights to the film remained untouched until about the early 1950s. That's when a young, unknown filmmaker named George Pal got involved.

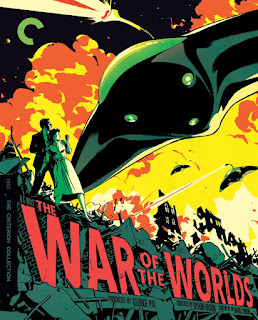

Here is where the work and scholarship of noted critic J. Hoberman does a greater service when it comes to filling in the gaps than I can. So it kind of makes sense to turn things over to him. The following information is provided by the Criterion Collection film and preservation website:

"The War of the Worlds...marked the apex of George Pal’s Hollywood career. But before World War II, Pal had been regarded as Europe’s answer to Walt Disney, at one point operating the largest animation studio outside the U.S.

"Born into a theatrical family, György Pál Marczincsák broke into the Hungarian movie industry as a designer and self-taught animator. In the early 1930s, he relocated to Berlin, where he pioneered the use of model animation at Ufa studios and then went independent. With its Busby Berkeley–like deployment of dancing cigarettes, his advertisement Midnight (1932) became something of a minor classic."Pal left Berlin for Prague after the Nazi seizure of power, moved on to Paris, and, largely employed by the Philips Radio company, established himself in the Netherlands, making puppet-animation ads and adaptations from The Thousand and One Nights. In 1936, Sight & Sound praised his “steady contribution to the cinema.” In 1939, he was recruited by Hollywood, where his small studio, affiliated with Paramount, became devoted to three-dimensional animations.

"During the 1940s, Pal produced over forty “Puppetoons.” The most notable, Tulips Shall Grow (1942), allegorizes Nazi brutality and shows the decimation of a peaceful countryside that presages The War of the Worlds...In 1949, Pal produced his first feature, The Great Rupert, directed by Irving Pichel and starring Jimmy Durante, along with the eponymous animated rodent.

"The credulous had difficulty believing that Rupert, who despite his limited screen time is responsible for the film’s several miracles, was not an actual trained squirrel. Indeed, Pal’s follow-up feature, Destination Moon, was celebrated for its vérité. Life magazine’s production story absurdly reported that “important scientific visitors” came to the set, to poke around “the painted craters just to get an idea of what a trip to the moon might really be like.” But Destination Moon had more to do with geopolitical reality than with extraterrestrial speculation (web)".

If all of this background information sounds like a rough tough slog to read through, I'll beg to differ up to a point. I'll defend it all at least as far as Pal's own experiences during World War II made a lasting impact on his mind, and hence the type of cinema he helped create as a result of it. It's a circumstance Pal shares with artists like Rod Serling and J.R.R. Tolkien. These are creators whose imaginations, like Wells, were shaped by the struggles against the various 20th century totalitarian regimes, and the results of those conflicts often play out on the page or screen for all them, in various ways. Nor are they at all isolated incidents of the same phenomenon. Indeed, it's not at all speculative to claim that a lot of the fallout (both figurative and in some cases literal) from the Second World War did a lot to shape the face and content of the Fantasy and Science Fiction genres that made all three men famous. This as an aspect that isn't lost on Hoberman as well. In the same essay quoted above, the critic points out that:

"Pal’s most expensive film up to that point, War was made during the highest anxiety of the Cold War. Armageddon was much on America’s mind. In mid-January 1952, as shooting was underway, the Federal Civil Defense Administration kicked off the Alert America Convoy, a film tour that would crisscross the country with a series of shorts promoting preparedness for atomic war.

"All year Hollywood germinated fantasies of the nation under attack. The first to arrive was Albert Zugsmith’s independently produced cheapster Invasion U.S.A., in which six citizens learn that an unnamed enemy has invaded Alaska and is bombing California. Flying saucers were a thing as well: In William Cameron Menzies’s richly paranoid Invaders from Mars, the first science-fiction film in general release to present aliens and their ships in color, a terrified child realizes that space creatures have arrived and are abducting humans, including his parents. Released in the U.S. not long after Invaders from Mars and several weeks ahead of The War of the Worlds, Jack Arnold’s 3D It Came from Outer Space provides a cosmic sense of our home planet. The aliens who crash-land in the great southwestern desert have no particular interest in Earth—they simply want to repair their craft and move on."In some ways, The War of the Worlds—which opened in the summer of 1953, a moment of relative calm following the inauguration of Dwight D. Eisenhower and the death of Joseph Stalin—synthesizes all three flicks. Like Invasion U.S.A. (but with far greater skill), it is a vision of apocalyptic destruction. As much as Invaders from Mars, it is a space-age horror film predicated on art design and spectacle, and, although more nationalist than It Came from Outer Space, it, too, has a planetary perspective".

I think author Stephen King is the one who helps put the finishing touches on the world picture Hoberman is describing. In Danse Macabre, King once wrote about how he was raised, along with the rest of his peers, in an atmosphere that was the perfect mixture of starry-eyed patriotism, and latent paranoia. "We were told that we were the greatest nation on earth and that any...outlaw who tried to draw down on us in that great saloon of international politics would discover who was the fastest gun in the West was (as in Pat Frank's illuminating novel of the period, Alas, Babylon), but we were also told exactly what to keep in our fallout shelters and how long we would have to stay in there after we won the war. We had more to eat than any nation in the history of the world, but there were traces of Strontium-90 in our milk from nuclear testing (9)". This then is the mindset of the times as both King and Pal knew them. In retrospect the truth seems to have been something like this. It was all a case of putting on a brave face in public, if only in order to hide away a gnawing sense of insecurity. This, then, was the cultural Cauldron of Soup out of which Pal's adaptation of Wells's story emerged.

Conclusion: A Mixed Bag Classic.

So with all this background information in mind, how does is all play out in the finished product? When I look at the film today, what stands out the most is a series of interlocking strengths and weaknesses. I can recall first catching this film on video cassette as a child, way back in the mid to late 90s. At the time, my initial reaction was more or less positive, as I recall. I guess you could say my take on the film today is still the same, yet with a few minor caveats. Let's start with the way Pal and his director Byron Haskin treat the story itself. The first thing to note about the story is the one aspect it has in common with all the other big screen attempts. It's something that vlogger James Sullivan has noted the best. "A rule of thumb for adapting novels in to film," he says, "is usually to remain as faithful to the novel as possible. But with all the various interpretations of the H.G. Wells classic...there seems to be an exception to this rule. With this story, it seems like the further away you are from the novel, the better off you are. But if you stick too close to it, you're in a world of difficulty (web)".With that logic, you could argue that Pal and Haskin are playing to the best strengths possible. They move the story's main setting from the Victorian England of the novel, to the early Eisenhower era California for their film. In place of Wells's anonymous journalist who narrates the action as it unfolds around him, we have Gene Barry's Dr. Clayton Forrester. And since I know I'll probably get flamed if I don't bring it up. Yes, the name of the main character from Pal's film was later used as the primary antagonist for the first few seasons of Mystery Science Theater 3000. What's kind of sad to realize is that this seems to be as far as most modern fandom can go with this flick, and its a shame because there at least something going on with the Haskin film than just a future pop-culture reference. In addition, there's the way the alien invasion itself is handled, and what can be learned from how Pal and company stage it. Rather than landing somewhere in a field of Great Britain, it's a small town located anywhere on the outskirts of California and Oregon. Rather than Wells's pre-Edwardian stock company, the first to discover the Martian comet are proud representatives of the 1950s B Movies, complete with the Dashing Young Scientist, the Grizzled Army General, Your Friendly, Local Neighborhood Preacher, the Small Town Sheriff Next Door, and last yet not least, the Hero's Heart-Palpitating Love Interest.

This last role is the one that stands out from all the rest, if merely because she is the one other character in the story who is given just as much of a focus throughout the plot of the film as Barry's character. She was played by Ann Robinson, and while I've heard complaints that she checks all the boxes of your typical era specific damsel-in-distress role, I will have to give Robinson this much credit. She does play the part with enough skill that I'm able say I at least got a sense that I was looking at a character, rather than just a stock role. In fact, while I outlined the majority of the cast above as if they were just stick figures in a cardboard puppet theater, the truth about nearly of them is a lot more complex than ordinary typecasting. As Sullivan noted in the link above, what's interesting about Haskin's film is the way it seems to know how to borrow and condense the same set of characters from Wells's novel.In fact, people like the General and the Preacher are, in a sense, repurposed straight from Wells's novel. Even Robinson's Love Interest has her analogue in the original book. In this sense, it's not a case of Haskin and Pal butchering the text. All they can do is try and find the proper expression for Wells's idea in a modern context. What that means in practice is a film that manages to find ways of hitting all of the major plot beats from the book, while still maintaining an identity of its own. For instance, once the Martian shuttle crash lands in field outside of Anytown, America, and we're treated to a few bits of banter and character establishment, we are confronted with a moment that is straight out of Wells's story. It's the moment when the Mars cylinder opens, and what look like the eye of some exotic, mechanical fish or snake begins to emerge from the hull buried in a crater. Three unlucky Red Shirts are on hand to act as cannon fodder for the plot, and while the setting and the accents are different, the scene that plays out once our Unfortunate Trio realize they have "visitors" is very much the same basic setup that you'll find if you go back and read the book. It's also perhaps the best scene in the movie.

Even once this sequence is over and done with, it can just be maintained that Pal and Haskin are doing their earnest best to keep to Wells's original structure as best as possible. Once the fate of the Red Shirts has been discovered, 50s audiences were then treated to what truly was one of the first big-budget spectacle battles (or first skirmishes, to be exact) in the history of Sci-Fi cinema. It's here that Pal is allowed to show off his prowess as a special effects master, and to his credit, his work does manage to leave an indelible impact. We're given our first sight of the Martian war machines, and the design for them has gone on to become iconic. They're these sleek, manta ray cobra like contraptions that float on the thin air like ghosts. It isn't until they let loose with their heat ray and ship's blasters that you find out just how deadly accurate those things can be, as the Preacher learns to his misfortune.

I can recall watching this whole sequence at or about ten years of age, and thinking it looked pretty impressive for an old movie. I can't say I know how these moments will look to modern viewers. However, to Pal's original audience, it must have had all the force of a revelation from a literal, other world. This was the early 50s, remember. The Bug-Eyed Monster Boom had yet to get really started, and it was thanks in part to Pal's efforts with this film that the whole craze eventually took off. To 50s viewers, this was the first time that the movies had ever given a concept from Science Fiction anything like an actual, serious treatment. And the fact that someone out there was willing to go that far just for the sake a fantasy idea was as novel as it was, at the time, unprecedented. It must have been that sense earnest seriousness that helped push things over from the realm of schlock, and into the precincts of respectability. Of course, the passage of time might have just tipped it all right back into the schlock ghetto. However, ask yourself if we would have even had a prop like the Millennium Falcon without the efforts that Pal tried to put on the screen? Primitive or not, this whole film was a ground breaker.The first attack goes poorly for the human animals, of course, and then we're treated to a cat-and-mouse sequence that I just now realized might be a precursor to the kind of dynamics we would see in later films such as Night of the Living Dead. After making a run-for-it from the field of battle, Our Brave Young Scientist and His Gal Friday must try and evade the clutches of a Martian hunting party by taking shelter in an abandoned farm house. The setup itself is practically a cliche at this point, and yet what's interesting to note is that, once more, this is an element that was already present in the Wells novel. If you stop and do the math here for a minute, you'll soon realize that technically this means that we have Wells to thank for giving us the basic outline of the Zombie Apocalypse, as well as that of the Outer Space Invasion. It's a two-for-one deal that I don't think anyone has ever realized the pedigree of until just now. If anything, it proves there's not that much new under the Sun, and that sometimes even the best genre tropes had their start on the printed page, before their breakout performance on the big screen. It also technically makes Wells a pioneer in more than one, or multiple genre formats.

It's also at this point where we begin to see a lot of the tropes that would come to dominate 50s Science Fiction making their first bows, and taking on a greater sense of dominance. Haskin's camera treats us to a lot of brief shots of generals standing around in rooms, trying organize troop movements and attack strategies. With the (at the time) future influx of incoming Kaiju movies from Japan, this brief sequence would soon become a standby staple in its own right. It is here where a further number of cliches become established, up to and including Our Hero Scientist dropping a Big Damn "Nuc-u-lar" Bomb on those Dirty Nazis from Beyond the Stars, only to have the invaders shrug it off like they were Bugs Bunny. This then transitions into the final moments of the film, and the overall picture is clear.

If the tone of this review so far sounds like its running hot and cold from one moment to the next, then perhaps there's a very good reason for that. I can't seem to quite make up my mind on this one. Rather, let's say that I have been able to form an opinion, and yet it comes in two competing, polar halves. On the one hand, there's a lot to like in this film. At the same time, part of me wishes there had been just a bit more. As things stand, I find myself on the stuck on a kind of mental seesaw, with my opinions ranging up and down on the same negative/positive polarity throughout the film's runtime. Nothing seems out of place, the film looks and plays perfectly fine as it stands. And for the longest time I could never shake the nagging sense that there was this one, vital, missing component that was out of place. This is something that becomes clear as the film heads into its final act reel. We're treated to a series of effective, apocalyptic visions as Dr. Forrester makes his way through the streets of a steadily crumbling Los Angeles. Aside from the White Flag meets Heat Ray encounter back at the start, it is in these final moments that film shows not just its real strengths, yet also a hint of what more we could have gotten, or perhaps what it really should have been all along. Perhaps Pal's film still remains unfinished.What I mean by that is while there is a lot to like in this movie, there may also be a few key elements that were never filmed, and yet probably should have made the final cut. Without this key ingredient, I can't shake the impression that I'm looking at a story that remains just half told. A moment ago I hinted that I really started to get into the picture during it final segment, the one where the protagonist is left to wander through a blasted out, desolate urban landscape as the Martian war machines lay waste all around him. The image itself is one of the defining tropes of Sci-Fi. What I soon realized is that this was probably the way Pal should have framed things from the very beginning. He should have made Haskin lean into the desperation and post-apocalyptic paranoia that such an image can engender in an audience. More than that, he would also have been following more closely the tone and action of Wells's original novel. I know that James Sullivan believes that adaptations of this book work best if you change certain things up. I can still see the logic of that idea, and yet what a re-watch of this film has taught me is that part of what makes the novel work so well is this growing sense of isolation and desperation, punctuated here and there by these occasional, big set-piece spectacles, or else a moment of slow burn, creeping terror, where the reader worries about what might be lurking in the shadows.

Its moments like the one in which the narrator finds himself barricaded in a house with Martians roaming the fields outside, that Wells was able to demonstrate his consummate skill as a storyteller. It showcases the equal amount of talent he had for bringing moments of Science Fiction and straight-up Horror together in a setting that blended the two seamlessly. It is precisely that quality that I think Pal and Haskin should have tried aiming for. It's nothing to do with the production quality of the images. We're not talking about star power or special effects here. Those are all just bells and whistles at the mercy of the script, or text. Rather what I'm talking about is the search that should have been undertaken for just the right series of plot beats. Those narrative moments that hearken back to Wells sense of creeping paranoia. These would be the narrative moments that are able to reach what Steve King refers to as "phobic pressure points (DM, 4)", that part of the mind and/or imagination where all the deepest collective fears of the audience reside. Any film or book that manages to reach within even a fraction of those points has to be considered a work of art in my book. It's a goal that Pal was able to reach later on in yet another adaptation of a Wells novel. In 1960's The Time Machine, Pal seems to have been able to locate where those pressure points reside, and is able visualize these phobias with the double gut punch of the Morlocks, and their subterranean underground passageways hidden just out of sight.

While some may complain about the effects of that later film, the way Pal frames Wells's nocturnal cannibals is in an aspect that turns them into a mixture of Tolkien's orcs, and the boogeymen that lurk in the shadows of your room at night. It leads me to believe there are some very good reasons for why King later went on to refer to the vents, tunnels, and labyrinthine sewers under his fictional town of Derry, Maine (home to Pennywise the Dancing Clown) as Morlock holes. Its easy to see how someone like King would be able to pick up on these vital narrative elements from both Wells and Pal, and later on put them to good use. This is the kind of narrative quality that I think Pal and Haskin were always searching for as they made War of the Worlds. The trouble is they always seems to have issues with being able to find it, and realize it on screen. There may be a number of mitigating reasons for this.It doesn't always have to be the director or producer's fault, after all. Sometimes it really might be a case of executive meddling. Pal, for instance, later claimed that it was Paramount studio execs who forced him to work in the Boy meets Girl love interest angle, and he forever maintained that this was a "creative decision" that he was dead set against, even going so far as to say that it hurt the picture. I don't think there was anything wrong with this particular plot element, in and of itself. It's just like I said above. Pal and Haskin still seemed to be finding their legs with this sort of material. The particular notes that Wells sounds in his novel would later go on to find a great deal of reuse in the Sci-Fi cinema of the 50s, and well on into today. The notes Pal was looking for were later seen played to as near perfection as possible by Don Siegal in his adaptation of Jack Finney's Invasion of the Body Snatchers. It was a note Pal was later to grow into with The Time Machine and others. In this early 50s film, however, he still comes off as a novice trying feel his way into this sort of material. Don't get me wrong, it's not enough to make the final product a bad film. It just feels less polished than it could be.

I think if I had a time machine of my own, one of the suggestions I "might" have made to Pal is rejigger the plot so that it more closely mirrors all of those elements that worked in Wells's original story, while at the same time letting the film keeps its own sense of localized identity. What might have worked is this. Spend just a bit more time letting the two main leads get fleshed out as characters. That way when it's time for the Martian to make their curtain call, the audience has got to know the two Love Birds enough to hope they make it out okay. I do wonder if focusing in on the military so much might have been a mistake. At the same time I might be able to see why Pal chose to go that route.

Pal's adaptation was made in the near immediate aftermath of the Second World War. It was a conflict that left Pal uprooted from his native Hungary. This was a very traumatic, even formative experience for the young artist, as Hoberman outlines above. What doesn't get as much detail is the way Pal would spend a great deal of his life working this whole experience out in his films. Hoberman mentioned a cartoon Pal produced called Tulips Shall Grow. While the critic does is hint at it, the whole truth is that it was Pal's allegory, even a kind of prayer for deliverance from the wrath of Hitler and the Nazis.In War 53, we see the former cartoonist revisiting this same trauma on a much larger scale. Indeed, the ending of this adaptation is roughly that of the same earlier stop motion animated short. It also helps explain the emphasis Pal places on the military presence in the movie. Part of it is the residual traces of patriotism that lingered for a time after the war. Another aspect of it is that its seems to be Pal's way of showing gratitude for the armies that saved him and his family. It makes the film not just explicable, yet downright understandable. The irony is what to do when it acts as an obstacle to storytelling that manages to deflate any of the tension that gets built up in a number of important scenes? There's not much else you can say to any of that except, "ouch"! For what it's worth, the way I would have recommended it be handled is closer, once more, to Wells's text. Let the two protagonists get separated in the first Martian attack. From here, the film would follow a lot of familiar plot beats from the novel.

In this alternate version of the film, there would be less of a focus on the military, and more that of a lone character just trying to survive. It would start with him trying to outrun the Martians, and then taking shelter in what by now has to be one of the oldest staples in Horror fiction, the Old Abandoned Farmhouse. Maybe he winds up there alone, or else "Dr. F". finds out he's sharing a hiding place with a crazy survivalist type, one of those Lone Nut figures that actors like Robert De Niro or Peter Boyle were famous for playing back at the day. This would a riff on the scene from the original Pal film. The difference here is that the focus is kept squarely on the plot elements of fear and paranoia. The tension in such a scene can be doubled if the main character faces not just an external, yet also an internal threat. While the Survivalist might seem calm at first, as things outside escalate, he begins to grow more unhinged, until at last he represents not just an immediate physical danger to Forrester. There's also the risk that all his noise making might soon alert the Martian sentries patrolling nearby.

This could have lead to a scene which might have been viewed with as much controversy as the Shower Sequence in Psycho was back in the day. It all hinges on how you play the ultimate fate of the Survivalist. The main character can knock him out to shut him up, and yet the ensuing scuffle draws the Martians attention. Or perhaps the Survivalist outs himself with all the racket he's making, and the invaders just take him out of the story themselves. You could also tip things into a full on Gothic mode by having "Dr. F" flat out kill the guy. This is one actual solution that the narrator of Wells's story toys with at one point. However, I think the the best course of action is to have brief moment of violence, one in which Forrester tries to subdue survivalist, only for Mr. Lone Nut to get the advantage of him. Just when it looks like the final threat of the film is going to be man himself, a Martian tentacle reaches in a grabs the Survivalist and drags him out of sight to his doom, leaving Forrester free to make his escape. From here is where the film would head into its final, post-apocalyptic third act.

I almost want to say that here is the part where you could easily splice in Pal's final reel in the finished film. Whatever the case may be, I'd argue that the final act should maintain a tonal structure similar to all that's gone before. There should be this sense of isolation and paranoia, and it should all be laced with a nice dose of suspense, as the protagonist shambles his way through the ruins of a human world, like a zombie who's lost his motivation. I'm not sure where I would go from here. I'm inclined to let Pal and Haskin's original 50s ending take over. The main point is that I hope I've at least given a suggestion of the more productive direction that they could have taken things in.

With this said, it's a mistake to call their final effort bad. There is nothing wrong in the strictest sense with their adaptation. Everything seems where it should be, the acting is professional, and while the special effects may seem primitive by today's standards, what has to be remembered is that they were all groundbreaking for their time. In other words, audiences would have seen it as the Star Wars effects of their day. There's really nothing to hate or even dislike in any practical sense. And, to be fair, I can't bring myself to call this a bad film. Nothing in it can qualify as an example of poor quality. The only real drawbacks I can find is that maybe Haskin and Pal didn't allow themselves, or else were prevented from going to just a few more darker places that would have helped amp the tension and stakes of the film up just a little bit more. Even this could stand the accusation of being little more than the nitpick of one, isolated fanboy, however. The objective truth is that George Pal's 1953 War of the Worlds stands as a classic of Science Fiction cinema. And it deserves to be rediscovered by audiences today.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment