As of this writing, Google Trends reports that just about 30 to 40% of people in America know who Winsor McCay is, or why he should be regarded as anything like a famous person. His prospects gets a bit better once you expand the picture to take in his global reputation as a whole. That still leaves him as an obscure name in his own country. If there's one thing a blog like this is dedicated towards, its unearthing the artistic names and glories of days past. And right now it seems like old, Winsor McCay is just such a name in need of a critical revitalization. Right now, the best place I can offer as a start would be to sort of repeat what I've already said about the artist in my earlier review.

"For every Henry James, or J.R.R. Tolkien, you have figures like McCay, whose life reads like a diary with several key pages either ripped or burned out. Sometimes this can be a deliberate move on the part of the biographer's subject, the perceived need for some sort of ill-defined privacy being felt as paramount over all other considerations. The irony being that such moves betray a lack of understanding of human nature, as that sort of behavior will always just tend to invite speculation about who the subject was behind closed doors. In such cases, I'm afraid the historical personage has no one except themselves to blame. They're always guilty of the old adage observed by P.T. Barnum years ago. "There's a sucker born every minute". Sometimes, however, the lack information comes less from deliberate obfuscation, and more through accidental neglect or circumstance. The latter seems to be the case with Little Nemo's creator. A lot of McCay's family and early history has had to be pieced together not because no one wanted any dirty laundry aired. Instead, it's due to the simple fact that all the helpful public records which could help fill in the gaps have been poorly kept over the passage of years.

"This has meant that all of his biographers have had to resort to the worst case scenario of speculation, based on what little resources are available. As a result, all that anyone can do is guess that maybe his family emigrated to the U.S. from Canada, where they soon managed to settle in the suburbs of Michigan, I think! Winsor's father, Robert, might have been part of a Masonic lodge at one point. Or at least that's one possibility. I'm not real sure, and neither is anyone else. There's so little to go on, that's the problem, you see. I will admit that if this is the case, then it does at least offer the critic one place to begin in terms of trying to figure out where the artist's early imaginative influences came from. If Rob McCay was a Mason, then he might have helped spur his son's imagination into life by regaling him with information about the meaning of Masonry, and the history and folklore behind all the symbols and imagery associated with this movement. Of course, you could also go further and surmise that another reason we know so little about McCay's early life is because his dad helped instill his son with the same Masonic tendency for secrecy and silence regard personal matters, except for or to any possible fellow initiates, and other Masons. However, that I know is little more than pure speculation on my part, and it doesn't really provide any answers, one way or the other."It's just as good an example of the kind of challenges you have to expect whenever tackling the life of Winsor McCay as a subject. For instance, it is possible that Winsor never knew just how old he was, because he never knew his date of birth. Nor have any reliable birth records ever been found that could help settle things. As far as McCay was concerned, he might have been born in the 1860s, or as late as the 1880s. He just never seems to have found out, and scholars theorize that part of the reason for this is because a series of fires that helped destroy a lot of public records over the years in Michigan might have help cut critics and biographers off forever from a lot of useful information. As a result, a usable portrait of the artist as a young child is hard to come by. His family is said to have settled in Edmore, Michigan, where he was born. Beyond that the rest is a blank slate, the kind that nature abhors, and so the imagination of the critic tries to fill it in. In my mind's eye, I just have this very stereotypical image of Winsor McCay as this young, tow-headed kid, all by himself in a field, drawing dust doodles in the dirt of the family farmyard. The very picture itself is practically an archetype, one meant to suggest a general idea, rather than the facts of an individual real life. The funny thing is I find myself wanting to stick with this Romantic image of the young McCay as living the life of this quasi-solitary, hayseed dreamer. It might not be the whole truth, yet perhaps there's an element of the truth in it somewhere.

All this is just to give an idea of how many gaps there are in the record of an actual life, especially when it comes to the vital question of what sort of artistic influences might have helped inspire the inner landscape of McCay's mind. It's frustrating as hell, yet I'd also be lying if I didn't admit the odd sense of fitness about the whole thing. It grants both McCay and his most famous creation this lingering air of mystery, like they're both hieroglyphs from a long forgotten language that we've lost the key to deciphering. It may be a hassle, yet it's also the kind you don't really mind, as that too has the ring of artistic appropriateness about it. It can still be a headache, on occasion, though. Let's take, for instance, the work that made him famous. If Winsor McCay is known for anything nowadays, then it's for the creation of a long-running newspaper strip known simply as Little Nemo in Slumberland.

Now, for the record, I can't tell whether or not McCay was the first graphic artist to try his hand at a concept like this. What I do know for certain is that he remains most well known for his efforts to translate the ideas of dreams in the comic strip format. Indeed, a good way to describe a series like Slumberland is that it amounts to a kind of fictionalized version of what's now known as a dream diary. The major difference is that it's hard to tell which of the dreams are based on real REM sleep experiences, and which are made up, and it's all told in what remain some of the most surreal, and creative visual landscapes that ever been set down on paper. The character of Nemo, and his adventures in his own world of dreams seems to have been something like a natural outgrowth of a previous creation, Dreams of a Rarebit Fiend. This was the strip in which McCay initially tried to see if it was possible to describe the contents of dreams and dreaming within a newspaper comics panel.

"The strip had no continuity or recurring characters, but a recurring theme: a character has a nightmare or other bizarre dream, usually after eating a Welsh rarebit—a cheese-on-toast dish. The character awakens in the closing panel and regrets having eaten the rarebit. The dreams often reveal unflattering sides of the dreamers' psyches—their phobias, hypocrisies, discomforts, and dark fantasies. This was in great contrast to the colorful fantasy dreams in McCay's signature strip Little Nemo, which he began in 1905. Whereas children were Nemo's target audience, McCay aimed Rarebit Fiend at adults (web)". It makes sense, in other words, to see this now somewhat obscure predecessor as a test-run for the now more famous series. The slow development of this idea was one of those cases of artistic serendipity.

In his book-length study on the history of animation, Wild Minds, critic and scholar Reid Mitenbuler devotes a few pages of his work to McCay, and makes sure to cite him as one of the main inspirations for the Golden Age of Animation. A lot of it, as he notes, was down to his breakout success with the Nemo comic strip. Mitenbuler writes: "The strip first appeared in 1905, six years after Sigmund Freud published The Interpretation of Dreams, which helped launch a popular obsession with the psychology of the (unconscious, sic). Once people read the book, they couldn't stop talking about their dreams and the notion that ideas and feelings might exist in a realm somewhere between magic and reality. McCay explored similar territory in his comic strip, playing with the familiar tropes of dreamscapes: falling through space, drowning, moving slowly while everything else around you moves quickly. Each week, his characters floated around outer space on milkweed seeds, on beds that acted like flying carpets, or in ivory coaches pulled by cream colored rabbits. These fantasies were always rudely interrupted by reality - falling off the flying bed and waking up in a real bed, or being jolted awake by a voice telling you it was all a dream. Adults enjoyed Little Nemo in Slumberland because it helped them reconnect to their childhood minds; for youngsters, it was a bridge to their blossoming adult minds (6)".The result of all this artistry was a brief span of time, in which McCay's creations were seen decorating the surfaces of lunch boxes, greeting cards, candies, and even several stage adaptations. Perhaps the biggest moment in Nemo's career is when he and several of his Slumberland friends were brought to life in vivid color animation. It was a pioneer moment in the history of film in general, and of animation in particular. McCay wanted to make a quick demonstration to audiences that this new form of storytelling was quite capable of producing genuine works of art. Not too long after, individuals like Walt Disney and Chuck Jones would go on to prove him right. While animation has found its place in the Sun during the intervening years, the great irony is that one of the artists who helped give it shape has since been neglected by the very art form he helped shepherd into a creative reality. Perhaps the real irony is that if Winsor McCay and his drawings have any reputation left, then its in the realm of animators and graphic novelists and illustrators. The rest of the world hardly knows about him.

The punchline here is that it was the very same format of the animated film which might have helped play a role in helping his name slip further through the cracks of popular memory. So far, there's been just one attempt at a film adaptation of Winsor's most notable creation. That would have to be Tokyo Movie Shinsha's 1989 production of Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland. The best way to describe that film these days is to think of it as one of the many old school releases that would appear seemingly out of nowhere, get touted as the next big thing, and then disappear down the memory hole after a year or two had gone by, except for perhaps a few snippets of film clips that manage to be ephemeral enough to make you wonder if it was real, or did you just imagine it? This was the quasi-ironic fate of a lot of major studio films back in the day. Looking back on them now, it's clear they were made with great expectations, and yet even those that did well on initial release have managed to leave not so much as a blip on popular culture. The other films that fit this kind of flash-in-the-pan phenomenon that I can recall off the top of my head, would be stuff like Terms of Endearment, or Fried Green Tomatoes.It seems like just a handful from that free-floating, early late period of Hollywood history have been able to leave much of any mark of impact (and here I am thinking of small yet stable efforts such as Field of Dreams and The Fugitive). There were probably more, yet they all fade into the fog of early adulthood. TMS's Nemo adaptation was one of the names on the half-forgotten list. Unlike the Costner and Harrison Ford films, this one had the bad luck not to catch anyone's interest. Where other animated fare from that period, such as Cats Don't Dance, are starting to build up a cult reputation, no one seems to remember or care much about the one single attempt at bringing McCay to the screen.

The funny thing is that one of few people who might have cared enough to take a stab at writing one of the many screenplays for this adaptation was a pulp novelist by the name of Ray Bradbury. By that point in time, as is still the case today, Bradbury's star had continued rising to the point where the former pulp magazine scribbler had become a world-renowned author who had summarily eclipsed McCay, along with a host of others, in the public consciousness. In a way, this may be the best possible explanation for why Ray decided to take a stab at adapting the Nemo comic for the big screen. You see, like all artists, Bradbury was very much the product of his influences, and one of them just so happened to be Winsor McCay. Like many kids growing up in the early 20th century, Ray would encounter Nemo and his imaginary friends in the newspapers that were either delivered to his family doorstep, or else found in the drugstore racks of his local neighborhood. In fact, Bradbury has gone out of his way in numerous interviews over the years to point out just how important the Golden Age newspaper comics were in helping him to develop his own voice as an author, and McCay was a major part of it.

If Ray was ever as dedicated a reader as he claimed to be (and there seems no reason to doubt this) then it makes sense that he's the type of bookworm who takes an interest in the audience's awareness of the art they consume, and how much of an interest they may take in a lot of these more obscure yet influential creators who have shaped the modern landscape of entertainment, and then been forgotten about. It just makes sense to me that it was a combination of feeling like a debt was owed to an artistic father figure, and a desire to see if he could revive McCay's reputation by adapting the Nemo strip, that Ray found himself signing on to try and pen a hopefully acceptable script that would help keep the memory of Slumberland alive. What the actual content of that script is, how good are its final results, and its ultimate fate are what we're here to talk about today.

The Plot Outline and Basic Setup.The book jacket synopsis from the Subterranean Press edition of Bradbury's screenplay reads as follows:

"Between 1905 and 1914, the American cartoonist Winsor McCay created a brilliant, years-ahead-of-its-time comic strip called, alternately, Little Nemo in Slumberland and In the Land of Wondrous Dreams. The serialized adventure recounted the dream journeys of a young boy (Nemo) toward the gates of Slumberland, where the Princess - his destined playmate - awaited. Over the years, this wonderfully surreal comic has exerted a considerable impact on modern popular culture. Among the readers entranced - and influenced - by this strip was another master fantasist named Ray Bradbury.

"Nemo! is an original Bradbury screenplay set in the lavishly imagined dreamscape that is Nemo's world. It is also a heartfelt act of homage to the genius of Winsor McCay. Beginning at the St. Louis World's Fair of 1904, the narrative moves through successive levels of Dream, encompassing moments of beauty, wonder, and raucous comedy while bringing a gallery of classic McCay characters - Nemo, the Princess, Dr. Pill, the sometimes villainous Flip - to vibrant new life. Intensely detailed, as colorful and absorbing as the best of Bradbury's fiction, Nemo! is both an unexpected gift and a unique collaboration between two of the 20th century's most distinguished - and inimitable - creative spirits".

If nothing else, at least a description like that can be said to have done its job. It was enough to get me to fork over enough to buy my own copy and see for myself. In the plot summary's defense, it does tell the truth, up to a point. We do get the cast of characters promised, and even a few that were never even hinted at, leaving a bit of discovery to be made here and there. As for the bit about the narrative moving "through successive levels of Dream"? Well, I suppose that's one possible description of what happens in the published script. Even if that's the case, it's also sort of where we run into our first major problem with this story. Before that, it almost seemed like we could have been going to some interesting places. Instead, the audience runs into an ironic situation, where the payoff of the story somehow fails to deliver on its setup. This results in an intriguing opening act that simultaneously winds up leading to nowhere in particular. It's the main problem of the story, and the result is jarring.

It's a shame, because those opening moments contain a lot of promising story material in them. We're introduced to Nemo and his life in the waking world in a way that helps give us what might be called a first draft outline of who he is, what kind of challenges his faces on a daily basis, and how all this might just play on an unconscious level in his sleep. It's important to bear in mind, however, that I said the opening act reads as a promising rough draft. It shows a lot of good ideas just waiting to be further developed. It also stops at being just that. The reader is shown that Nemo is the product of a stable and loving middle class home. We're also given hints that he might be something a constant daydreamer, whose thoughts often wander off into utopian visions of the future. This results in the script's other promising character note. Bradbury depicts McCay's protagonist as someone who shows the potential spark of being a great future inventor someday, kind of like a child-sized version of Thomas Edison with a bit more of an imaginative streak in him. This concept appears to be original to Ray's screenplay, as the original comic strip went very little into Nemo's day time life. What we do learn about the character in the comic strip is greatly inferred from the nature of his nighttime fantasies.The way McCay paints Nemo is as a boy on the cusp of transition from starry-eyed idealist to just your average, disenchanted adult. The original comics thus play out as an extended sort of personal battle, as Nemo struggles to hold on to that important sense of childlike wonder. What Bradbury has done is to take this important, over-arching element, and find what seems to be the perfect way of expressing it outside the confines of the protagonist's head. Rather than being limited to the main character's imagination, we see how his interactions with the real world are shaping the way he relates to others, and the challenges of life in general. In that sense, Ray's ability to translate Winsor's concepts to script format can be termed a success. Just like in his comic strip incarnation, Nemo is shown to be someone desperate to make the world realize just how much of an interesting and enchanted place it can really be, and Bradbury is smart enough to allow us a scene between Nemo and his father where he explains a lot of where he's coming from, and what makes him tick. Ray presents Nemo as this budding genius with visions of technological advance and old time, nostalgic enchantment dancing around in his head.

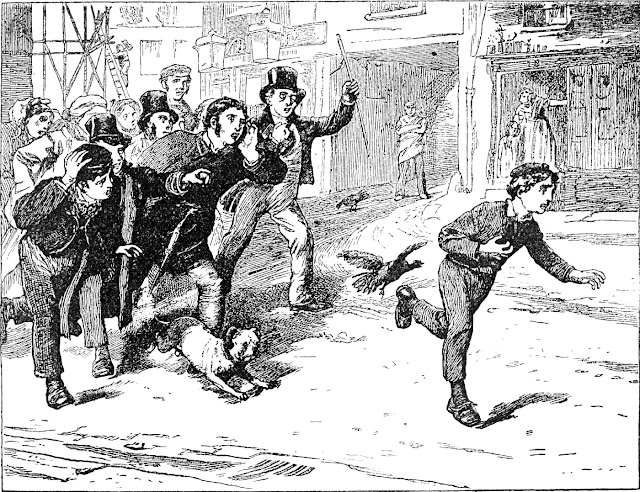

The screenplay subtly hints that Nemo is not just on the cusp of the first glimmers of adulthood. He's also at something of a personal crossroads, where the joys of childhood fairy tales are vying for equal attention with growing enthusiasm for a budding form of science fictional utopianism. All of this comes to a head when he enters the 1904 World's Fair Exposition. It's here that Nemo discovers both of his loves, Sci-Fi Futurism and Old World Fantasy mingled together in the perfect combination. These are all the best parts of Bradbury's script, and its shame to report that this is as far as it all goes. From here on, things sort of go downhill. The first hint of a misstep comes as Nemo makes his way to the fair. On his trip to the exhibition, he gets accosted by a bunch of local neighborhood, maybe even school bullies. Now this scene is interesting as much for what it hints, as it gets wrong. There are about three or four of them, and Bradbury's description of them is intriguing. Take, for instance, the first lines of dialogue from this group of "gentlemen", as they begin to address our wandering hero."First Bully: Hey, here's that new guy on our block! What's your name, sissy?

"More Bullies loom, jostling him. But Nemo seems not to hear. Walking slowly on, they must follow him.

"Second Bully: Nemo! Hey!

"Third Bully: You'd think he'd never seen a World's Fair before!

"They unbutton his coat, flip his tie, but he strides on.

"Fourth Bully: Look fast! Tomorrow they tear it down!

"Nemo (aghast): No!

"Seeing this has gotten through to Nemo, the Fourth Bully grabs the model airplane out of Nemo's hands.

"Fourth Bully: Yeah! It'll all look like THIS!

"He crunches the plane, hands it back. Nemo can only stare at the ruined plane in his hands, and the buildings around him.

"Nemo: No! It's got to stay up - forever!

"They jostle him, laughing, jerk his tie, pulls down his cuffs, rip a button off his shirt (15-16)".

Now my immediate response to this whole sequences is fairly simple. It looks as if the writer might have the beginnings of a good idea on his hands, and yet it needs work. Part of the reason for this is contained right in the dialogue itself. The first bully to speak addresses Nemo as if he's never met him before. He even goes so far as to label him as the "new kid" in the neighborhood. The problem is the reader (or would-be viewer) sees this plot element tossed up, only to have it contradicted the very next minute when the next bully to speak addresses the protagonist by his own name. The first thing any of these 'lost boys" say tells us to think the main character is about to encounter a new challenge. Then it's as if the whole scenario switches gears and its seems as if this is nothing new for our hero. The way the punks target Nemo, the words they aim at him, and the general way approach him gives the impression that we're dealing with the latest act in a scene that has happened before. The reader comes away with the impression that Nemo has encountered the wrath of these pint-sized thugs on numerous occasions.

So why open with a contradiction that gets dismissed as soon as its uttered? I think there's a logical enough explanation for all this. Bradbury began assuming that the plot was going in one direction, only to have the story itself try and take over, leading to narrative developments, and character dynamics on a different course than what the author expected. Now to a fair, this is the sort of thing that happens all the time in the act of creative writing. Sometimes, when the writer thinks they have a good idea of where things are going, the story can sometimes "come to life" on them, for lack of a better word. A good example of this happenstance from literature is when Tolkien bumped into the character of Aragorn in the Prancing Pony, at Bree. By his own admission, Tolkien wasn't expecting to find him there, and yet it was clear to him that this new character was there for some reason, so he just continued writing to find out what that was. The result of that pivotal choice has gifted us with one of the greatest, and most memorable of action heroes in the history of Fantasy fiction. There's a bit of a lesson to be learned in cases like this. I called the choice pivotal, and that's just what it turned out to be.My own experience as a reader has been that when a story starts to come to life on its author is also the make-or-break moment. That crossroads place where the artist has to decide whether or not they want to follow the lead given by the Imagination. If they can do that, then while nothing is guaranteed, you just might have the makings of a real story on your hands. It worked once for Tolkien, no reason it can't happen to anyone else. What makes artistic decisions like that so important in retrospect is that its one of those choices that helps determine whether the next ink stained wretch to come along has it in them to be good at this writing gig. Peter Straub, in his introduction to a non-fiction essay collection, Secret Windows, addresses just this moment of creative choice when makes what I believe is an important observation about it all. In his introduction, Straub makes an important distinction between, as he calls it, "inventing" and "discovering". In no uncertain terms, Straub makes it pretty clear to the reader that while "invention" may have its place, it is a second-rate form of writing, at best. Or else its a borderline form of malicious lying at its worst. Discovering a story, is a whole different matter.

For Straub, as for authors like Coleridge, to discover a story is the real act of narrative creativity. That's where all the true writing is done for him, in other words. And he's just about as committed to this basic, Romantic notion as was the author of Kubla Khan. He's not saying its impossible to excuse an honest misstep or two, here and there. It's just that if you pile up one misstep after another, sooner or later a good critic has to ask the question whether or not someone is losing the whole damn plot. I want to say that Straub's words here ought to be treated like an unspoken maxim. Because they might come in useful when making a final judgement call on the Nemo script. Now it's true that Ray is guilty in the snippet above of making what amounts to a literary flub. It is just possible to point out how big the mistake is by going right back to the opening sequence of the script. It features Nemo having a dream about being chased by these very same bullies, which in itself implies a he has undergone a long history of abuse at their hands. Still, you can't accuse Bradbury of inventing in these early moments. It's just one simple mistake, probably born of a fuzzy memory, and a desire to "get it all down on paper".

Problems like this can be easily dismissed. The kind of thing that can be corrected without much fuss. It's what second drafts are for, after all. The real issue is with the main plot of Ray's script, or rather a general lack thereof. When it comes time for the actual story to kick in, things seem to be going alright, at first. The transition from the waking state to that of dreams is handled in a pretty creative manner. Bradbury frames it all so that at first the audience is not sure that anything is out of the ordinary, letting the dream elements slowly sneak up on both the audience and protagonist. So far, so good. This positive suspension of disbelief continues when the viewer is introduced to a new character with the significant sounding name of Omen. He tells Nemo that he'll be his guide to Slumberland, and immediately the narrative's main action begins. Again, things start out as pretty smooth sailing, literally. It's here that Bradbury allows his readers to enjoy one of the key features of the original McCay comic. Taking us all on a good and harrowing flight through the night sky, as Nemo and Omen turn the bed into a kind of flying carpet that takes them off and up into the literal stratosphere.In some ways, this might be the best sequence in the entire script. It's also the most visually dynamic. It's easy to imagine all the camera angles and neat animation tricks that could be used to bring this part of the story to life. The imagery of the whole scene would have been lifted more or less wholesale from the likes of J.M. Barrie, and yet if done right, they could achieve an identity of their own, one that does signal its influences, while also making each of these old elements their own thing, thus passing a torch, and marking out a new legacy for itself. I just wish that everything to happen afterwards could live up to it in some way. Instead, here is where the script drops the ball, and I'm not sure whose fault that it is. Now to be fair, even our first initial introductions to Slumberland itself are pretty good. The entire layout of the setting winds up as an amalgam of things that Nemo has drawn upon from his real life experiences. It's based predominantly on the 1904 World's Fair Exhibition, and goes on from there to expand it into an entire dreamscape made up of different fantasies and backdrops, and settings.

There's no way you can ever realize all of it on the big screen. And the good news is you don't have to. You just need to get as much down as can work for the story. One of the good things I'm willing to say about the 1989 anime release which we did get is that it really does seem as if they did a good job in trying to bring McCay's original drawings and illustrations to life. The key thing to remember here is that the visuals alone aren't enough to make for a good film. It's the story that holds everything together. In the case of Bradbury's screenplay, it's after Nemo and Omen land on top of the dream city's main palace roof, and meet Dr. Pill (a character from the original comic strip) and are escorted down into the hallways of the kingdom itself that everything turns into one, big, jumbled up mess of a plot.

In some ways, the movie script becomes difficult to explain, because it literally starts veering from one set piece to the other, with very little in the way of a plot thread to connect it all together. First Nemo is escorted to meet the ruler of Slumberland, King Morpheus (no not that one). Then almost immediately, this encounter with someone who sounds like he could be at least some kind of important player is cast aside, and we're in a typical, slapstick, hijinks in the kitchen situation. It's the kind of scene that's been played countless of times in Screwball Comedies, and Looney Tunes and Three Stooges features. This time, since its a dream, there's really no limit to how zany you can make it, and Ray gives the animators plenty of fuel to work with in a kitchen that is powered by elephants, dinosaurs, and even a dragon at one point. It's fine so far as it goes, and perhaps at this point the problems aren't quite beginning to register. It isn't until we reach the character of the Princess, and a banquet scene that follows her introduction where you kind of begin to see cracks forming in the plot, and the real false notes begin.

Let's take the Princess of Slumberland as a first instance. Here is how Bradbury introduces us to her, as an everyday element in reality, which in turn goes on to form the basis of Nemo's dream:

"Nemo hesitates, puts the coin in the slot. Machinery grinds and tinkles, purrs and intercogs in secret stuffs.

"And from the interior base of the large crystal, an incredible figure appears, rising frozen, pure white, dressed in frosts and snow drifts and powderings of winter. When she has fully risen, and stands waiting, as 'twere, to be set free to dance, or at least move.

"Nemo, incredulous, puts out his hand, touches the crystal and:

"As if on cue, she turns, lifts her arms, motions her hands, dances, the pure essence of winter. She has her own music, of course. Attention John Williams! Winter music here!

"The Princess of Winter stops.

"Nemo reaches out a tremulous fingertip to touch:

"And she moves again, melting away into spring leaves, faint green traceries, the look of trees in her limbs, the flow of wind in great clouds of maple leaf in her hair. Music!

"She freely dances and stops. Again, Nemo touches the crystal.

"And again the Princess changes, as the green turns to the ripeness of summer, the color of peaches and apricots in her brow and cheeks, the tincture of cherries in her lips, her hair filled with summer sun, her eyes as bright as solar discs! Music. Summer Music! She dances.

"And stops. And Nemo, delighted, touches the crystal a final time to see:

"Her change to the last season of her ritual, as summer browns and burns itself into autumn, and her hair darkens with a tossing away of multi-colored leaves, and her eyes become smoke-fires, and her cheeks the color of red-orange-brown autumn leaves, and her hair smokes away like a great autumn bonfire. As she dances, music, autumn music."Until at least, the four dances of the four seasons finished, she freezes back into her original white snow winter shape and slowly, as Nemo watches, dismayed:

"Sinks back down into the base of the crystal, gone. The last music ends.

"Nemo, his face burning with love, turns his pockets inside out: Nothing!

"He looks at the empty crystal and whispers:

"Nemo: I'll be back. I will!

"He backs off.

From his POV, as the camera recedes, the crystal ball swirls with light and shadow, now echoes of winter, sounds of autumn, faint musics of spring and summer (22-24)".

Now, to be fair, that is perhaps, another one of the few scenes that can be said to work really well. It's a great example of writing, scene setting, and character introduction, in a manner of speaking. We haven't really met up with anyone, and yet this moment shows Bradbury playing to his strengths as an author. He's planted this suggestion of this kind of ideal girl in Nemo's head, and it's set up so brilliantly, because now we, as the audience are gearing ourselves up for meeting her later. Because that one moment tells us to expect that simple, flickering, dancing image to sooner or later come to life in the dream. Here's the catch though. The setup for the for this character is like its own, quiet moment for us to marvel over. When we get to the actual Princess, however, this is what happens:

"As the Princess studies (Nemo's out-stretched, waiting to take her hand, sic, she) takes it, hesitates, and then-

"Gives it a huge bite!

"Causing Nemo to yell...

"...She makes a final gesture of her snowy hand and BANG! the band drums and brasses, and the parade to the banquet starts!

"The Princess leads the way, Nemo one step behind.

"Nemo: Do you...er. always bite strangers?

"The roses bloom in her cheeks again, for a moment. She does not look at him, but the blush shows her feeling.

"Princess: Only the ones I like (77, 78)".

To flesh out this idea further. A good character note for her would have involved her with yet another figure from the newspaper strip. He's this bumbling schemer named Flip, and he's very much the comic relief in the original Slumberland series. And the way you could use him to put some narrative meat on the bones of the Princess would be to have a scene where she denounces Flip and kicks him out of the royal court while they're both in public. Then later on, she takes Nemo to a secret meeting with Flip, and its revealed that the two of them are really very close friends who often join up to go on these wild, and fun escapades together. There is at least on idea that carries with it the promise of a fully developed character. And all this is something the characters in the script lack, and it suffers as a result.

It doesn't really get any better from there. At a certain point, the story itself just kind of breaks down into nothing more than this series of vignettes and set pieces that don't really go anywhere. First Flip loses a powerful maguffin somewhere known as the Well of Dreams. Someone has to go and bring it back. The catch is the Well is very dangerous, no one has ever returned from that place. So on and so familiar. That's really all the rest of the script has in terms of plot. It's just this bare bones skeleton of an idea. And all Bradbury can find to do with it is to use it as a coat rack for various gags, and visual set pieces. From this point on, no one character is ever given a chance to stand out in any meaningful way. They're just yanked around from one spectacle to another with little to connect it all together. There's very little else to describe, except to note that it all reads as a good example of bad writing.

Conclusion: A Very Rough First Draft.

Well, I think I might found the answer to all these question, and it's kind of ironic. Strange as it may sound, the short answer is that this might not have even been Bradbury's fault at all. It was all just a case of studio interference. To give a more detailed answer, we probably need to back up a bit and start at the beginning. Not too long ago I did a review of the atrocity that is the live-action Pinocchio remake. In that review, I made it clear that I couldn't find any good reason to hold the film's director, Robert Zemekis, responsible for the way that "anti-movie" crashed and burned. The explanation for this is because everything about the final product told me that, in the strictest sense, it couldn't be said to have had any director helming the damn thing at all. All the aspects of that debacle pointed to Zemekis not being the one with any real creative power, or input into the film's narrative. All of these vital components seemed to have rested in the hands of the studio itself keeping a tight grip of the steering wheel, and refusing to let anyone with actual talent chart any actual creative course.

It really does look like the same thing is what happened here, several decades ago, with Ray's Nemo script. It is just possible that all those glimmers of plot potential were a series of maybe good ideas that the author Something Wicked This Way Comes was looking to develop into a fully fleshed-out narrative. One with all the necessary ingredients of drama, characterization, and above all, plot development. By the time the finished script reaches its final page, however, whatever is left of any story has been chopped up and butchered like a steer in a cattle market. And it leaves hanging the question of why it all went to shit so darn fast? The best answer I've got is that what we're looking at is yet another story in the occasional, ongoing annals of stories from Development Hell. In other words, the reason the Nemo script fails is because it was never given a proper chance to breath by the higher ups. In plain words, it was interfered with by studio meddling from near start to the finish. It ruined any potential for a good narrative, and the filmmakers left themselves nothing to work with as a result.It's one of the greatest stories of filmmaking irony around, and I do think that anyone who wants to gain a better understanding of how a good idea like this can go wrong should watch the following video for a fuller explanation of just how much insanity Ray had to put up with in writing just a single script:

If anyone bothers to stop and take a look at the resource provided above, you'll probably get all the answers as to how a script like this could go so wrong. Basically, when Ray was tapped by Gary Kurtz (one of the producers of the film) to write the screenplay, he was basically being tossed into the middle of a pressure cooker that had been simmering for some time, way before he even showed up. The biggest strike against his chances of helping to churn out a success was that by this time, everything was way too far into development hell for Bradbury's effort to make a difference. By that point, too many cooks had been added, and the broth was beginning to spoil. In that sense, all Ray could do, very much against his will, was just help everyone sink the movie's chances into a far deeper pit than the one they'd started out with. In fact, the video above provides an anecdote from none other than Brad Bird which I think neatly sums up the kind of problems the Nemo project was facing. "Their experience working on Little Nemo is as follows, in Brad Bird's own words. 'Jerry Rees and I worked on this for about a month. We were sent down because we were told the project was drifting, and we were asked to check it out and give our assessment. So we went down to a building they'd rented in Hollywood to check out what was going on. And we're staggered at the quality of the artwork on the walls. "We were floating around, talking to people, casually. Asking them about what they were doing. And they said: 'We're just illustrating what Ray Bradbury is writing'. We walked around some more among the jaw-dropping imagination and talent on display, and ran into Bradbury himself. We remarked about the terrific work, and asked Bradbury about the story he was writing for the film. 'I'm just putting in writing what these wonderful artists are drawing', he said. Jerry and I looked at each other: Uh-oh"! The rest of the narration from the video does perhaps the best job of providing an answer as to why Bradbury's script went nowhere in an ironic number of ways. "Whatever was going on, Little Nemo was a project of constant turnover, meandering design, and exponentially little progress (web)".Every single word of that observation syncs up well with the contents (or lack thereof) from Ray's script. The punchline is how it's also these very same qualities that make me realize I can't quite blame the screenwriter for the story's failure. The whole screenplay might be an over and underdone mess, yet the reasons for it seem to lie well outside of Bradbury's control. While the makers of the video resource above are careful to tread lightly when it comes to figuring out who is responsible for what went wrong. Everything they show me leads to the inevitable conclusion that the ultimate failure of Ray's script, and perhaps of the final product as a whole, rests with the film's main producer, Yutaka Fujioka. Throughout its production history, Fujioka is the one who remains the primary driver and overseer of all that transpired when it came to working on the Nemo film. What it all seems to have come down to is a clash between personnel and creative differences. The main impression I get is that it was all, ultimately one-sided on Fujoika's part. People like Bradbury, Gary Kurtz, or even Hayao Miyazaki would bring him all sorts of possibilities for how the story could go, and Fujioka would keep brushing them aside, because none of them seemed to fit whatever he was looking for in the project.

That's not the most helpful or encouraging artistic business environment to work in, and it didn't seem to take long for the strain to show up both on and off the screen. If I had to make a guess at the ultimate reason why Bradbury's script, and the final film never reached their full potential, then perhaps the true answer is that what we're dealing with is a familiar case of artistic ambitions coming up against human limitations. For the longest time, it seems as if the Nemo production was the one idea that Fujioka couldn't seem to let go of. Everything about the way he mismanaged the story indicates that it either was or soon became this object of obsession for the producer. Which sort of makes me wonder why on Earth didn't he just try his hand at a story treatment himself, if he felt so personal about it all? That's a question I don't have an answer to, I'm afraid. What does seem clear is that once Fujioka got the basic concepts of Nemo and Slumberland in his mind, it's like he couldn't figure out what he really wanted to do with them. As a result, it was like time stood still, and everyone else was dragged along for the ride. Somehow a film was released from all this turmoil, and what we've got now is kind of interesting.The best result Fujioka was able to give viewers was called Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland. I have memories of catching TV promotions for it back in 1992, and being not quite able to make sense of it. When I got a chance to see it for myself, I'll have to admit its sort of a mixed bag, and that's not all too surprising, given the behind the scenes problems it had. It's basically this generic quest film containing a few interesting ideas that are never given enough time to flesh themselves out. In other words, its a riff on the kind of script Bradbury wrote. Still, it might have some redeeming qualities. The best act, in my opinion, could be the final one. This isn't that much of a surprise, considering its the one moment in the film where the people in charge realized they needed a plot work with. Whatever strengths it may have, however, the truth is that McCay, Nemo, and Slumberland are all still out there waiting for a better shot at a true movie adaptation that will do them all justice. Until that time, the entire property remains stuck in limbo. The funny thing is Ray's script might contain one or two ideas that could form the seed bed for the right kind of story that McCay's characters deserve.

Everything that's good about Ray's script can be found in its opening pages. This is where he either makes, or finds a number of creative choices that go well with the Nemo character. For instance, the idea of letting Nemo be an instinctive inventor, someone who is charmed by the likes of both Edison, Einstein, and the Brother's Grimm in equal measure. There's something about the idea that carries a fitting sense of dramatic resonance. It's like we're finally starting to get a handle on what makes this kid tick. It also seems right to imply that Slumberland itself is a mental extension of the main character's experience of the World's Fair. So is the concept that Nemo is the victim of bullying at school, and just in general. All of these ideas form the perfect basis for a script containing each of the necessary ingredients for a good story. I think a better way it could have gone was as follows.

After the bullies have roughed up Nemo, and broken his model plane, they then run off, jeering at him, laving Nemo to pick both himself and the remains of his own aspirations up off the floor. This should be our first big character moment. The audience ought to see that underneath the tears he's holding back that Nemo is also filled with a great deal of anger over his mistreatment, especially when it comes to people mocking his own ideas about how to build a better future. For the moment, our sympathy is with him, as the anger starts to build behind his eyes. Then, it's like he's run out of steam, as his temper deflates, and he goes back to picking up the pieces of the broken model. From there, we follow Bradbury's script as Nemo takes in the 1904 Exposition. His reactions are a mixture of awe, wonder, and fascination, mixed in with a bit of sadness, knowing that most of it will be torn down. Just like in Ray's screenplay, the audience should be given visual clues that the content of the World's Fair are beginning to shape what Slumberland will look like in Nemo's dreams later on. We go with the original screenplay here all the way up to Nemo's encounter with the model of the dancing Princess figure.Here is where our first main deviation comes in. As opposed to Bradbury's script, Nemo is kind of smitten by what he's seen. He reaches out and tries to take the hand of the imaginary girl, only to realize there's not even a plastic figurine there. The whole thing is an intricate projector image. Realizing this, Nemo waits until no one is around, and filches the projector for himself. We then cut to him making his way back home, having successfully carried the projector out of the World's Fair. Before he can reach the safety of his own doorstep, the bullies corner him one more. They ask him questions like, "What ya carrying' there, sissy"? At first, Nemo acts as he always does in the face of their threats, saying something along the lines of "Lay off. Leave me alone. I wanna go home, etc".

Here, however, things change once the bullies snatch the projector containing the images of the Princess out of his hand, and ask "What do we got here, eh"? Nemo is horrified. "Give it back", he demands! This just invites further taunting from the bullies. 'Aw, and what if I want to keep it for myself"? "You can't", Nemo insists! "Hell", the lead bully says, "what if I was just likely to", and here he lets the project fall apart as he drops it on the ground. All the bullies share a cruel laugh at this prank, as Nemo bends down over the wreckage of the magic lantern. We see him trying to rearrange the shattered pieces of glass together, briefly reforming the image of the Princess, only to have the lead bully stomp it to pieces right in front of him. This triggers a flare of temper that Nemo has never quite experienced before. He leaps for the head bully, knocking him to the ground. In the process, Nemo gets a lucky shot out of the gate, as the bully doubles over, shouting that he thinks his leg is broken.

|

The other gang members look stunned at this sudden reversal, before Nemo turns a wrath-filled gaze on his other tormentors. In an instant, he lunges at the group, throwing punches in a rapid fire succession that catching them all off guard, allowing him to land a few quick punches that gains him a swift edge in the fight that ensues. While the gang members recover and try to fight back, getting a few good cuffs and nicks in, it ultimately doesn't go their way. Nemo's sudden berserker mode turn makes him not feel whatever hits get delivered his way. Instead, he keeps battering his tormentors down. Things take an interesting turn when they appear ready to surrender and cry uncle. They may be ready to retreat, yet Nemo's actions make it clear that as far as he's concerned, things are just getting started. This becomes obvious, and dangerous, once Nemo pins another one of the bullies against a wall, and starts pummeling him.Just as he's about to aim a punch square at the kid's face, he's grabbed from behind by the first bully, now limping, yet trying to get him away from the others. This is a mistake as Nemo goes right for the first bullies leg, sending him to the ground once more. Nemo then reveals a side we've never seen, and perhaps even one he's never suspected from himself before. The minute the bully is down, Nemo proceeds to deliver a series of swift kicks to the ribs. It isn't until he hears the lead bully cry out in genuine pain that Nemo's own face almost literally shifts back into the one we're all familiar with. It is Hyde one second, and then Jekyll the next. Now instead of a growing, deranged look in his eye, we now see just a very confused and frightened kid. Nemo looks around, almost uncertain of where he is, and all the bullies are now drawing away from him in real fear. One of the others is helping the leader to his feet, and Nemo watches in stunned silence as they run off as fast their leader's injuries can allow.

It is here that what might be termed a Miyazaki moment can be inserted, if you want. It would feature just Nemo, outlined by himself on the neighborhood street in the fading dusk of an otherwise normal afternoon. Looking at him there, staring off after the bullies, and then into the distance, you wouldn't think a dangerous fight just went down, or that the kid left standing might have been in danger of losing his mind. After the contemplative pause is over, Nemo bends down, and starts to collect the pieces of the projector and its images together. We'd then make a quick cut from Nemo bending over the wreckage, to a shot of his hands reassembling the image of the Princess suspended in the glass projector slide.

We pull back to reveal that Nemo has been performing this delicate operation in the privacy of his own room. The projector itself has been stashed into a rucksack hanging over his desk chair The only thing that looks out of the ordinary about this scene is the tell-tale sign that the back of Nemo's hands betray his recent scrape. Some of the knuckles are red raw, and one of them even sports a cut on it. Beside the image of the Princess is the broken remains of the model of a futuristic looking airplane. Nemo gingerly takes the repaired Princess and places her in the drawer of his work desk. After taking one last, longing look at the girl in the picture, Nemo hears his dad's footsteps approaching, and quickly shuts the desk drawer. He then stashes the projector in his closet, and returns lightning quick to his desk, and takes up repairing the plane as his dad comes in. This introduces the final key scene before the main action starts. Nemo and his dad have a heart-to-man talk before bed. His dad initially stops in just to check up on him, like normal, and then notices the cuts and bruises on his son's hands.Nemo insists that it's just from mistakes in trying to repair his airplane model. His dad studies him for a nervous second, then seems to go along with it. Though there is just the hint he is letting things slide, for now anyway. With the heavy topic shelved, Dad takes in the rest of his son's room, which is covered in other kinds of inventions, self-made devices, illustrations of great and exotic looking cities, and a few other airplane models similar to the one on the desk. It becomes clear that Nemo is, or could be this scattershot style prodigy. Someone with a lot of brains who can turn his focus to a lot of things technical, or artistic. This can be seen in the way a lot of Nemo's designs mix achievable fact with unadulterated flights of fancy. Certain city plans can turn in an instant from a skyscraper out of Metropolis into an enchanted castle by Disney. His father takes all this in with a mixture of puzzled admiration, yet there's not doubt he's proud of what his son has been able to achieve, so he speaks to Nemo about what he hopes to accomplish with all of this? His son tells him that he's really trying to figure that out as well, himself. All he knows is that he'd like to make a contribution to the future.

He cites people like Edison or Da Vinci as examples he hopes to live up to. His father points out how that sounds like a rather tall order. At the same time, he doesn't discourage Nemo from trying to find out what achievement of his could be important for generations to come. Before he leaves, Nemo asks his father an important question, one that's been nagging him since he got home this afternoon. Can people capable of great inventions ever be wrong? In other words, is it possible for people who are good at inventing stuff to not just be prone to error. Is it possible for something to be wrong with them? Can an inventor ever be bad? This is as close as Nemo dares come to broaching the subject of his berserker fight with his father. The old man admits its a difficult question. He admits as how we might have all been better off if people like Winchester hadn't created the modern gun. He also points out how airplanes themselves could become weapons in the right, or wrong hands. This last notion catches Nemo off guard, making him visibly uneasy. His dad notices, and asks if something is wrong?Nemo replies by wondering if there may be people out there who would like to invent for the sake of all the wrong reasons? To tear the world down, instead of building for the future? His father allows as how that's a possibility all men have to take into consideration. He then drops a bomb that confirms his son's worst fears. He wouldn't be surprised if some folks like to create new inventions out of pure spite and meanness. Nemo's eyes go wide at this, and Dad misreads this as mere normal fear, and reassures his son that he doesn't have to worry about being anyone like that. Nemo chooses to put up a convincing brave face, and his dad gives him a goodnight hug, and leaves. When he's gone, however, the look on Nemo's face is one of vague apprehension. He looks at the models and designs that litter the walls, corners, and ceiling of his room, then down his bloodied and bruised hands once more. The sight of such a glaring contrast makes Nemo shove his hands back in his pockets with a guilty look.

He turns his gaze back to the airplane model on his workbench, and goes back to hunching over his desk, repairing his invention. It is at this point that we transition from waking life to the dream portion of the story. Like in Bradbury's script, the transition from awake to asleep would happen with Nemo tinkering at his desk. His eyes would slowly begin to droop until he props his hand in his hands on the desk. Soon his eyes close, and his breathing becomes rhythmic. Then the following happens.

Throughout all this, Nemo's reflection has been visible in the background, in a wall sized dressing mirror off to the side of the desk. We see Nemo's mirror image copy every move the real boy makes, down to him falling asleep at his workbench. After a beat, however, Nemo's reflection opens its eyes, looks about, sees his original slumbering all by himself, and grins. This would be our introduction to Omen. He's a character original to Bradbury's script, however while in that draft he remains this neutral good-ish figure, here he is given a much more substantial, antagonistic role. He starts by tapping on the glass in order to get Nemo's attention, and from there proceeds to lead him through the mirror into Slumberland. It's here that all the main action would commence. We'd start with Omen leading Nemo outside of the looking-glass version of his own house out into a blank, white space with nothing in it. Omen would then challenge Nemo to see if he really is a great inventor. Nemo would counter by creating Slumberland, first one bit at a time, and then gradually unfolding it all at once.

This would have been the first great set piece of the film, allowing the audience a chance to see McCay's original phantasmagorical cityscapes and designs come to brilliant through the work of the Miyazaki and his Studio Ghibli team. We would also be introduced to the inhabitants of Nemo's dream city, including the likes of King Morpheus, along with the boy's ideal dream girl, the Princess. She's given the name Camille in the TMS anime, and for the sake of convenience, it's something I'm willing to include in this alternate scenario. In addition, we'd also meet Dr. Pill and the free-loading Flip. The King and his daughter would tell Nemo that they are the inhabitants of the future, and yet things are still not complete. In order to be a real society, they must have an inventor, someone who can help bring their city and its people to life. Morpheus therefore gives Nemo two tasks. The first is to act as Slumberland's royal court magician, helping to build up the city and its territories to their full potential. The second command the dream monarch gives is that Nemo be his daughter's royal playmate.From here, we would follow Nemo, accompanied by the Princess, Omen, and Flip as he sets out to both discover and design the rest of the dream kingdom. Here is where Omen begins to show the first of his true colors. As Nemo goes about creating greater and grander visions of Slumberland, the Princess is the one who keeps suggesting all the best ideas that will guarantee good results. Omen, meanwhile, will keep nudging our hero into making the sort of creative choices that sound either reckless, or potentially harmful, such as new types of weapons. This is where Flip surprises everyone by coming in handy. He may be there just to goldbrick and cause mischief, yet he's smart enough to point out the flaws in Omen's schemes, and helps Nemo keep away from a bad influence. Omen finally gains the upper hand when he manages to make a successful appeal to both Nemo and the Princess that its best if they come up with a scheme that will help make Slumberland safe. Nemo and the Princess are starting to go along this suggestion. While it is Flip the trouble-maker who is the lone hold-out of the group.

He's ignored, and Nemo agrees to Omen's idea. As he does so, the sky in which they have been flying over the make-believe lands lights up as unseen anti-aircraft bombardment erupts from below them. Nemo's dream plane takes damage, and all of the characters are separated in the ensuing crash. When Nemo comes to, he seems to be awake, and in his own bed. Everything looks normal until he hears a noise rustling from under the bed. He grabs a baseball bat and peeks at what might be hiding there. Instead of the Boogeyman, it is just Flip who emerges from under the bed. First he congratulates Nemo on being an even bigger dummy than him. Second, he informs him that everything in Slumberland has gone wrong. It's getting so a guy can't pull an honest, decent prank there anymore. Ever since he agreed to Omen's terms, all of Nemo's inventions and creations are being used to ruin the dream kingdom. Nemo asks Flip to take him back to Slumberland, and the two set off once more.

This would showcase the other decent sequences from both the finished anime, and Bradbury's script that are worth saving. It starts when the bed itself grows legs and marches first out of the house, and then down through Nemo's street. That entire image is drawn direct from McCay's comic, and is perhaps the best thing in Fujioka's movie. We then switch to Ray's script as the bed leaves the Earth, and carries us through a harrowing flying sequence back into a desiccated dream world. All of the great edifices and cloud capped towers either lie in ruins, or else they have been remodeled into technological nightmare versions of themselves. The new look of the dream land should borrow heavily from both Metropolis and Brazil. All the warmth and color ought to be drained out of everything the characters see and here. Perhaps the most interesting idea is what happens when they rediscover Morpheus and Camille. Rather than being the rulers of this city, they are found living in a simple wood hut as paupers, with no seeming recollection of having ever been in charge of this world. They do admit that Nemo seems familiar from somewhere, and they are both opposed to what Omen has done to their home.Together, the group of four decide to try and take a stand against Omen, and try and rescue Slumberland. That's about all I've got in terms of an actual plot to go on, I'm afraid. There's not much more tell, except that I know the great showdown of this never to be filmed version features Nemo squaring off against Omen, his own dark half, that's willing to use his technical prowess and artistic knowledge for all the wrong ends. The final battle would take place on a monorail that is careening out of control as two sides of the main character's psychology duke it out for supremacy. Those seem to be all the major ideas I could have for improving the story, really. All else I could add might be things like a bit of fun where Nemo thinks that Camille might have reverted back to her Princess form, only it turns out to be a version of the famous Metropolis robot sent as a trap to do him in. The one other thing I would have added to all of the alternate script outline described above is that as Omen's true nature gets revealed, his appearance ought to become more sinister and ominous to reflect all of Nemo's bad qualities. By the time we reach the showdown on the out-of-control monorail, Omen should be illustrated as no more that a dark shadow whose only visible features are a set of grinning teeth, and a pair of burning red eyes. That would be my idea for a pretty decent antagonist for the movie.

I think the best thing about the kind scenario I've outlined above is that it answers one of the concerns that was first expressed about the actual anime project back way back in the 80s. It shows how a story centered around a dream of the main character can work if done right. In this case, by having the dream center around a moral choice the hero is struggling with, what happens inside the confines of his own mind will determine the sort of future actions he takes, and the kind of person he will become in real life. In this version, Omen represents a temptation Nemo has for squandering all of his gifts as an inventor and illustrator on petty schemes for revenge, thereby turning him into an even worse bully than the one's tormenting him in his waking moments. Indeed, one of the villain's final lines would be to try and cajole his better half into going along with a path a retribution against the world, because, as he says, "It's the wave of the future, Nemo"! By defeating this warped and crooked aspect of his personality, Nemo is able to wake up the next morning with a changed, even wiser outlook. He's found out that it's important not to give up on your dream, yet also make sure you treat others well along the way. That's pretty much the extent of any good ideas I might have for a Slumberland adaptation.

I just think the real shame here is that a genuine talent like Ray Bradbury was never given the chance to allow his imagination free reign on this one. I've read enough of his work to know the guy was one the great American literary geniuses. It's the kind of artistic gift that works best when there's no interference bearing down on him. In that sense, the TMS production was the worst place to go to try and adapt an idea like this. It needed slow, and careful deliberation. Time enough to find out where all the vital sources of inspiration in the story could lie, and let the tale bring itself to life. Like I say, it's too bad we got none of that. Instead, all we're left with is a hodge-podge of characters and settings that never coalesce into something resembling a legitimate narrative. The upshot is that as of this writing, we're still having to wait for anything like a possible, definitive adaptation of Winsor McCay's Little Nemo in Slumberland. I'm real sorry to learn that Ray Bradbury never got the chance to pen that script. He would have been perfect for the job. Though it's still no reason to stop bringing dreams to life.

No comments:

Post a Comment