It was a result of the first great video game boom during the 80s. It's how we got stuff like Pac Man, Space Invaders, or Super Mario Bros. As the games got more sophisticated, so did the graphics, and pretty soon there were arcade boxes that offered games functioning as tie-in materials for favorite shows on TV, like the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Hell, even Michael Jackson once had an arcade game dedicated to him, that's just how crazy and interesting things used to be back in the day. Sure enough, Springfield's favorite family also got in on the action at one point. It was this beat-em-up brawler were you got to choose between any of the four members of Che Simpsons as you battled your way through town in order to rescue the baby, Maggie.

I'm not sure the of exact place where I first saw that particular bit of shameless merchandising. I think it could have been in the lobby of a long defunct theater chain, or maybe a local pizzeria type place. My clearest memory, however, is of catching a brief glimpse of the game's setup, and finding it kind of intriguing, I guess you could say. As far as first encounters go, that probably sounds simple enough. Except there's just one problem. My mind has played a further trick on me. That's not the real first time I ran across The Simpsons at all. Before that it all must have started off as a sporadic series of passing chance encounters. Here's where the history begins to get sketchy. Beyond a few crucial snapshot remembrances, I don't think I paid enough attention to all the times I was ever alerted to the presence of America's Favorite Dysfunctional Family on the airwaves. It's possible the first time was catching a casual glimpse of a quickie promo on the TV at one point. This, in turn, might have been followed by the first spate of toy commercials. I know at some point I wound up the owner of a rubber-plastic Bart figurine. Though it's been so long that I no longer recall how I got hold of it, or what's even become of it today. It might even count as a lost collector's item these days, for all I know.

After that, things begin to come into a bit better focus. Not a lot, though better than where it all started. I can claim with certainty to have caught the tail-end of the episode known as Bart Gets Hit by a Car. It's the one that ends with Homer and Marge commiserating with each other over a pint at Moe's, remember? Marge just blew the family's chance on winning a hefty wad of money from Mr. Burns in court. There was this shady ambulance chaser named Lionel Hutz who'd finagled it so they could all hit the jackpot in terms of a monetary settlement for the "damages" done to Bart at the episode's start. All they needed to make it work is ensure that everyone was on the same page, and give the same false testimony. Bart and Homer are onboard with this scheme. Lisa and Marge, however, are not. And it's Marjorie's decision to tell the truth which causes the court to turn against them. The show then ends with Man and Wife apologizing and patching things up together at Springfield's best watering hole.This is all stuff I found out about later on. I first came in at the end, like I said. Right at the point where Homer looks Marge right in the eye, and realizes that he still loves her with all his heart. He tells her as much in front of all his drinking buddies, and everyone cheers, and decides to celebrate with a round of Duff Beer. Hard to believe that's how it used to be, isn't it? This was all in the future (once upon a past) for me, at the time. Back then, all I saw was another snippet of a burgeoning pop culture phenomenon, and I still didn't have a clue what it was about. The funny thing is I probably would have remained clueless of all this if I hadn't left a video cassette recording long enough to capture a rerun of the episode where Marge decides to get a job at the Nuclear Power Plant, and winds up catching the eye of Homer's boss. I forget the name of the episode after all these years, yet I can still remember a lot of the shenanigans that went on in it. It included a subplot riff on the story of The Boy Who Cried Wolf, involving Bart. It's the one that ends with the couple being serenaded by Tom Jones, only he's being held captive by Mr. Burns as the result of one of his attempts to win her over to his side.

I don't think there's much of anything new about the patchwork story I've just told. Odds are even the world is full reminiscences just like mine. All of them, when placed together side by each other, would amount to little more than an anecdotal history of how America first came to know what used to be considered the funniest, and most clever sitcom satire in history. At least that's how it all started out. The key thing to note about that little bit of shared history written above lies in the way it was told. I was having to work from memory the whole time just to get the facts straight, which is telling. I also had to stop every now and again when I realized I hadn't told the whole story. There were gaps in my history with The Simpsons that needed shoring up in order to give an accurate picture, and this is something that's even more significant. All I was trying to do was recount how I came to know about a very famous (once popular) TV show, and yet it took effort because of how much time had lapsed between when it all happened, where I am now, and how much energy I gave to remembering it all.

The whole process teaches a sort of unintentional (yet very real) lesson on the sometimes perilous nature of human memory. It's a natural enough aspect of life, and something that we all have along with other mental faculties, such as the Imagination (if there even is anything natural about make believe, or remembrance for that matter), and yet it's something you sort of have to work at if you want it to function properly. If I had to give a good description of what a memory does, or is supposed to be, then I guess a good way to describe it is to call it a way to capture all the important moments of things that go to make up a life. How much any of us is able to recall important events from our past probably says a lot about what we value, or hold to be important. The intertwined subject of the persistence of memory, or the remembrance of things past is a topic of great concern to a writer like Anne Washburn. It forms part of the core of a play she wrote not too long ago. It concerns, of all things, nothing less than The Simpsons, the show's legacy, and they way we recall it in our collective memory. It's an intriguing fable of remembrance, persistence, and the way we tell stories to each other, and how the best tales manage to survive through the passage of time. It's called Mr. Burns: A Post Electric Play.

The Story.

Note: the following synopsis is provided verbatim from The American Conservatory Theater's Words on Plays program notes. This article is indebted to the Company's help and insights, even where the conclusions reached may differ from the views expressed in the program listed above. Thank you."Act I.

"The United States has experienced a widespread and catastrophic nuclear-plant failure that has destroyed the country and its electrical grid. After the disaster, a group of five survivors - Matt, Jenny, Maria, Sam, and Colleen - gather around a fire and recount the episode entitled "Cape Feare" from The Simpsons, Matt Groening's popular animated series about a dysfunctional American family and the zany community of Springfield. In the episode, young Bart is stalked by the murderous Sideshow Bob. The episode contains a dense collection of many stories that came before it; most prominently, it is a riff on the 1991 Martin Scorsese film Cape Fear (starring Robert De Niro), which is a remake of the 1962 film (starring Robert Mitchum). The episode also contains kaleidoscopic cultural references to Mitchum's earlier role in The Night of the Hunter, as well as Gilbert and Sullivan operettas.

"As the survivors attempt to remember the events of the episode, they discover that memory is unreliable, disagreeing over who said what and how significant punchlines were worded. They are interrupted by the entrance of a new survivor, Gibson, who offers them information about what's happening outside their camp and tells them stories of destruction, evacuation, and power plants taken offline. The survivors have filled their personal journals with the names of their loved ones, as well as the names of everyone they have met after the disaster. It is customary to compare notes with any new person's list of loved ones, and vice versa; the survivors go through this ritual with Gibson, but find no crossovers in the people they've encountered. The group soon comes back to the original topic of conversation: "Cape Feare." Gibson helps them remember a punch line, the words of which they'd previously mangled. Act I ends with Gibson entertaining the rapt survivors with a Gilbert and Sullivan song: "Three Little Maids from School Are We," from The Mikado."Act II.

"Seven years later, the shared experience of recounting "Cape Feare" has been formalized into a much larger endeavor. The same group of survivors has formed a theater company that specializes in performing a small repertoire of Simpsons episodes, spliced in with "commercials" about bygone luxuries (hot baths, cold Diet Coke, and Chablis, to name a few) and pre-disaster top 40 hits (sung a cappella). As they rehearse together, we learn that Simpsons episodes are being performed by others as well. Lines from the episodes are currency; the characters compete with several itinerant troupes for the best and most accurate lines, paying audience members who can offer them long-forgotten Simpsons snippets, for which they will then have exclusive rights. The troupe is anxious about whether or not their shows are good enough to maintain an audience. In the outside world, food is scarce, nuclear plants have completely melted down, and chaos and danger reign. Act II ends with the troupe under attack by a mysterious, unseen, group of criminals. Shots ring out and many of the troupe members fall.

"Act III.

"It is 75 years after Act II. The Simpsons has assumed mythic proportions, and the "Cape Feare" episode has transformed into an epic opera in which Homer, Marge, Lisa, Bart, and Mr. Burns (the show's heartless nuclear power plant owner, who has since replaced Sideshow Bob) are figures cobbled together from elements of the television show and the aftermath of the apocalypse; in addition to the morphed version of "Cape Feare," the chorus recounts the names of people killed in the nuclear meltdown and dramatizes events of the past several decades. The musical is a mash-up of hip-hop, Gilbert and Sullivan operettas, and dialogue that the original survivors in Act I spoke around the campfire (2-3, web)".

Some Interesting Pop Cultural Context.

The first thing you have to understand about a play like Mr. Burns is that it does not exist in a vacuum. Washburn's theatrical riff on the No. 1 Family of Dysfunction is perhaps best described, in the strictest sense, as merely the most notable effort and product of a much larger phenomenon. The trick with a story like this is that in order to get a proper read on it, you have to take a brief detour into the cultural context that it originally emerged from. I'm not talking about the world of the Theater here, by the way. The play itself exists less as a creation born from the traditions of the Stage, and more as the result of one medium colliding with an otherwise disconnected show biz product, or pop culture artifact. The whole thing started during Washburn's student years as a Bay Area theater artist participating in a number of creative exercises while attending the A.C.T.'s Young Conservatory program. "The culminating exercise was to imagine that a great plague had taken hold of the world, and the YC participants were all doctors who had to envision what they would do in the face of disaster," says Washburn. "It seems appropriate that I'm coming full circle to do an apocalyptic play at A.C.T (4)". This is the initial inflection point for the idea of the play. It functions as our first piece of the puzzle in getting a proper sense of what kind of play we're dealing with here. The second bit of information that helps us along is a description of the type of drama that Anne Washburn specializes in."Washburn's plays are a testament to her interest in how, why, and when stories are told - as well as how they mutate over time. Her range is versatile, running the gamut from a musical adaptation of Euripides's Greek tragedy Orestes to a linguistically complex dark comedy about globalism and cultural confusion (The Internationalist), gothic vignettes that evoke the scariest horror films (Apparition), and a droll feminist epic about dictators and the women who love them (The Ladies).

"Washburn's stories are difficult to categorize, but they might best be described as comic dramas and tragic comedies about a global state of affairs. In Mr. Burns, large scale catastrophe underpins the story, but Washburn's world doesn't offer up the familiar wasteland we've come to associate with the apocalypse genre. This landscape isn't riddled with zombies, plagues, and brute survival...The desperation of her characters is rendered in their passion for the story (a persistently memorable episode of the The Simpsons entitled "Cape Feare") that they attempt to cobble together from memory. This pastime provides the backdrop for the world of the play, in which the death, continuity, and resurrection of specific stories is directly tied to the character's survival (ibid)". Those words were written way back in another time and world known simply as 2015. As such, it provides us with the third puzzle piece we need to get a better picture of Washburn's story, and the way it does so almost by accident is perhaps the biggest clue to just how far the world of pop culture fan art has developed by leaps and bounds.The specific idea and phrase that the program writer(s) seem to be grasping toward is the fact that it makes the most sense to call a writer like Anne Washburn an almost textbook example of what's now known as a Mash-up Artist. Both the term, and the basic idea behind it, have a very interesting history. The term mashup or mash-up originated within the music industry. Also called "mash-up", songs within the genre are described as a song or composition created by blending two or more pre-recorded songs, usually by overlaying the vocal track of one song seamlessly over the instrumental track of another. To the extent that such works are "transformative" of original content, they may find protection from copyright claims under the "fair use" doctrine of copyright law. Adam Cohen of the New York Times notes that even before that, "the idea of combining two data sources into a new product began in the tech world" before spreading to other media, including book publishing. The term appears to have first been coined in a review of Seth Grahame-Smith's 2009 novel Pride and Prejudice and Zombies. Initially calling it a "parody" and "literary hybrid", Caroline Kellogg, lead blogger for Jacket Copy, The LA Times' book blog, later describes the work as a "novel-as-mashup (web)".What we're dealing, in other words, is the still emerging birth pangs of the kind of new form of artistic expression that could only have come about during the process of the digital age. That said, mashup culture does have its antecedents in the works of Dada surrealists like Marcel Duchamp (web). While both the term and practice might have originated in the world of music and painting, however. It has by now branched out as an all-purpose method of aesthetic expression, which has gone on to have its share in all of the major fields of art. This also includes the field of creative storytelling, both on the page, screen, and stage. This is where Washburn's efforts come in. Though in order to get the full picture of what she's up to with her mashup play, we need to now focus in more on the very subject she's tackling with her production, and here's the part where the story gets real interesting. The Simpsons don't need much of an introduction at this late date, though perhaps some level of apologies are in order. I know I'm late to the party on this, and the sentiment has become a broken record cliche by now, yet it's still true that when you talk about the show today, all you're discussing is something along the lines of the burnt out husk of a fallen giant. There was a time when the series was the premiere venue of satire and entertainment in the history of American comedy. At least that's how it all started out to begin with.

As time went on, for lack of better words, things changed. The gist of the situation is summed up in the course of a video essay entitled, The Bizarre Modern Reality of the Simpsons. In a previous video, the documentarian behind both pieces neatly outlines and juxtaposes the glaring dichotomy between how things were to the way they are now in just two simple terms: Simpsons-mania vs. Zombie Simpsons. Both video essays are worth a view in their own right, and I really do have to pause here to give a shout out to Super Eyepatch Wolf, the creator and critic of each. His acumen in examining the rise and fall of Springfield and its First Family are phenomenal and convincing. Needless to say, a lot of this article has been influenced by his work. In the first essay linked above, for instance, Wolf asks a very important question, and it's one that has a surprising relevance to the efforts of artists like Washburn. The question is, "Why? Why is The Simpsons still going? The Simpsons is still airing, with its most recent...season seeing the most iconic family of the 90s contorted and shoehorned into the topical issues of 2019. Marge enters a "Reality TV" show. Homer gets a job in a self-driving car factory.

"And Bart becomes woke. I'm not even going to make the argument that these episodes are bad. Just that they are not The Simpsons, and how could they be? The Simpsons is now over two decades removed from the era, culture, and people that made the show what it was. And so what's left is nothing but an imitation, with the TV ratings of this most recent...season hitting an all-time low. And so, why is it still being made"? Wolf's answer is pretty simple. "The Simpsons' name is still lucrative, and what's more, despite the fact that season 30 was one of the lowest reviewed seasons in the shows history, it's still pulling in viewers by the millions. And as long as that viewership remains higher than Fox's other shows, and those profits stay consistent, Fox will keep syndicating the show, and The Simpsons will be trapped in it's zombified, money-making form. And this, unfortunately, is the sad, modern reality of The Simpsons". Wolf is quick to point out that it's not the whole story, however.

"There's this other side to The Simpsons in 2019. One that is weird, and fascinating, and exists in a world entirely outside the scope of the show...People have been taking The Simpsons and re-appropriating them for decades, even long before the internet. The Simpsons having a rich history of bootleg merchandise. But what the internet did () was take that process and hyper-charged it. Anyone can now make their own version of The Simpsons and upload it. And, in doing so, creating an entire online sub-culture of people repurposing The Simpsons in strange and fascinating ways". This is the contextual milieu out of which Anne Washburn's play has emerged. "The bizarre world", as Wolf calls it, "of what The Simpsons has become on the internet". It's a phenomenon that was happening long before Washburn ever got caught up in the whole movement, and hence got the idea for adding her own little riff to the festivities. And yet it's her work that perhaps best exemplifies this entire trend.

Conclusion: A Remarkable Pop Culture Mashup Story.

In terms of setting and genre, there's nothing all that original to be found. Perhaps one of the perfect ironies of the play is that it doesn't choose to linger about or bother with all the usual tropes associated with After the End narratives. The play script barely mentions anything that we've come to expect from this kind of scenario. We're given a brief scene of people squaring off with guns, and that's about it. Even then, it doesn't wind up going the way you'd expect. For a story set in the aftermath of a civilizational collapse, there's little that the author does with it in terms of any of its conventional uses.

That's because Washburn seems less interested in how the world ends, and is more focused on what remains. Her focus isn't on how things fall apart. Instead, she's captivated by the ways people can build things up from scratch, with nothing more than the simple power of stories. Here's where the actual originality of Washburn's conceit comes into play. While it's true that a fallout of some kind has taken place before the curtain opens, all of it is relegated to an off-stage event that is easily hand-waved aside. Instead, both the opening and second acts jump right into the middle of a group of survivors who don't fall to bickering or taking the usual satirical, brutalist jabs at each other. All Washburn does is focus on the group trying to comfort one another by recalling an episode of their favorite TV show.As we'll come to see, by the end of the play, this simple act of exchanged kindness goes on to have a surprisingly valuable legacy, as it winds up signaling the first attempt of humanity to regain itself, and rise from the ashes. This is the ultimate focus of Washburn's play, and it's also what marks it out as different from all the other examples of this genre that usually get name checked on a list of Sci-Fi favorites. However, if the author's story does qualify as post-apocalyptic, then it's natural low-tech approach puts one more in mind of works like Riddley Walker, The Stand, or even Hansel and Gretel than it does the normal idea of what this type of story should be. I suppose a good way to describe it is to claim that what Anne Washburn has done is to create one of the first post-apocalypse stories for the rest of those who don't care for it. As far narratives like this go, Washburn's efforts are incredibly user-friendly. The play's focus on friendship, and the way in which a shared passion for good stories can not just help to forge new allies, but also a new, possible civilization, helps to make this one of the lightest, perhaps even the most delightful aftermath narrative out there, as strange as that may seem.

It even sounds incredible that someone could find that much light hiding in what many have often considered to be a fundamentally dark genre. And yet that's just what the writer has been able to pull off. In that sense, perhaps the most remarkable thing about a play like this is how it's willing to just let the sun first shine in through the cracks in the wall, and then burst into a sense of genuine warmth near the end. These are all the initial aspects that make the play work so well as it does in its initial setup. It leaves us with just the mainspring inspiration, or pop culture engine that powers the entire narrative from start to finish. The initial action the kicks off both the story and its ultimate consequences is a discussion of the aforementioned Simpsons episode, "Cape Feare". It all begins with a group of survivors trying to recall the episode, and what happens in it during the course of a single night. We follow along as all the participants begin to mount an imperfect, yet entertaining reconstruction of a shared narrative that they've all enjoyed as a touchstone in their lives, and as they begin to do so, the ultimate themes of Washburn's story slowly begin to come to the fore, and make themselves known.

This meaning is best on display in the play final third act. It's at this point that the story switches focus from a rag-tag group of survivors trying their best to recall their favorite TV show from memory, to an actual show-within-a-show re-dramatization of the "Cape Feare" episode. This time, however, it is done with a very interesting twist. Washburn has performed a re-imagining of the original show script. In this version, what viewers are given is less a straightforward retelling and more of something along the lines of what I almost have to call a Neo-primitive Myth. There's a time jump between the second and thrid acts, you see. When a cue card at the very start of the last half informs the reader that 75 years have elapsed since act II, a whole 82 years from the start of the first one. In that time, within the post-apocalyptic secondary world of Washburn's story, humanity has still survived, and so, in a way, has The Simpsons. However, it's a version of the characters and setup which is pretty sure to be all but recognizable by Matt Groening, and everyone else who ever worked on the series, for that matter.With the collapse of digital and film media, combined with a new world still in its infancy, all anyone can remember about the past (even something as simple of a satirical sitcom) becomes a combination remnant forever at the mercy of mankind's collective (and often unreliable) memory, and also something of a totem or symbol imbued with a great deal more significance than any of the original showrunners were planning. In the absence of social media, and a lot of other modern conveniences, the field of the arts seems to have gone somewhat back to its roots within the world of Washburn's play. What we're treated to with this aftermath version of "Cape Feare" is what Springfield and its denizens would look like if guys like Shakespeare and Sophocles, or perhaps even the anonymous, ancient collaborators who collectively helped to birth the Medieval pageant plays of the 11th and 12th centuries, had managed to get their hands on it, and tried to retell it in the only way they knew how.

If there is any satirical element left in this new version of The Simpsons, then it's not expressed in the way it was back in the TV show. Instead, it's as if the First Family of Television has been regressed, perhaps a better word is collapsed back into their original, almost pre-modern, primordial forms. Their personalities seem more or less the same (for all intents and purposes, at least) and yet its the way in which all of these familiar attributes get expressed that shows how the focus of Groening's original creative idea has shifted over a span of imaginary time which makes all of the real difference.

Bart, for instance, now seems to have a lot more in common with the initial Trickster archetype from which he originally sprung in the first place. There's something almost Minerva-esque about Lisa, meanwhile. Marge now has a great deal of Demeter about her. And Homer's antics and nature now seem to cast him more in the older, traditional notions of the Fool. It's as if, in the absence of modern distractions, all the old artistic ideas have begun to bubble up once more to the surface, and along with it once familiar modes of creative expression and perception. What we're presented with, then, is a re-telling of an old TV episode in the mode or style of an ancient, allegorical stage fable. What happens when you turn the Simpsons into figures of myth is a result that I don't think I was quite expecting.

Even the language of the play takes a left field turn, as Washburn's cast of character shift from the downright Altman-esque style of regular, over-lapping, everyday dialogue of the opening scene, or the more scripted and fictionally appropriate methods of the second part of the story. In the finale, every line of dialogue is spoken in what can only be described as a postmodern form of Blank Verse. It exists somewhere between song and spoken word, a kind in-between half poetry with obvious traces of Shakespeare and Sophocles in it, yet the volume and eloquence have been turned down, and rendered in a more modern diction. That's not a complaint, by the way. It's an actual, deliberate choice on the author's part, and it makes sense for the context of the narrative. Even if the arts in Washburn's secondary world are starting to remember its more classical past glories, it still makes sense that any dramatic diction that such a society would come up with would result in a kind of patchwork quilt form of prosody, something between contemporary speech and poetry. It's as if the artists in this imaginary realm are are making their slow way back toward a lot of the older forms of dramatic expression, and yet at the moment, it's like trying to recall fragments of dialogue from a half-remembered dream.

This is a creative choice which plays in well with the logic of the story, as it seems like half of the arts in this post-nuclear fiction are the sketchy patches of collective memory. This also plays into how the story of "Cape Feare" itself has evolved over the centuries. What we're greeted with now is a mythical allegory for whatever unseen fallout event has brought society to its current nascent state. Now the Simpsons aren't just meant to represent a satirical jab at the nuclear family. They're now symbols of mankind itself. And the plot no longer centers around a highly personal, almost isolated grudge match between a demented Sideshow Bob and Marge and Homer's son. Instead, we witness the entire obliteration of Springfield and its people by a genocidal version of Mr. Burns. In this alternate future, both of Kelsey Grammer's and Harry Sheaer's characters have been dissolved and transfigured into a composite of one another. The memories of the Simpsons, the original 1991 and 1962 versions of Cape Fear, perhaps even the obscure John D. MacDonald novel both were based off of, have been melded altogether into an almost homogeneous whole, resulting in a new monster for the family to run from.

This is no longer some petty, small town business man content with running his own little, personal fiefdom. This version of Burns has become the nuclear radioactive version of the thing hiding under your bed, just waiting for you to fall asleep and claim your life. He's become this Saturnine embodiment of nuclear fallout, and a way for the fictional civilization in the story to grapple with a lot of the darker aspects of the past. This refashioning of not one, but two characters is written in such a way that it's clear he's become a combination of this kind of folkloric bogeyman, while also serving in the role of a lot of famous monsters from the Horror genre. He's got this sort of built-in catharsis factor, something that helps the audience deal and come to terms with their own fears in a way that can be positive whenever its executed correctly. It's an aspect that all the great villains of fiction have in common, and this time it's Sideshow Burnsie who is given that particular role. In doing so, Washburn effects a transition from basic satire, and transmogrifies The Simpsons into the realm of the epic. It really is something you have to read in order to believe. It's not expected, yet it is impressive.

It's also here that the author herself is able to be of service in disclosing the meaning of her story, as she was gracious enough to share the ideas behind the text in an interview with Words on Plays. It's there that the author shares a great deal of insights into the thought process that first helped create, and later went into her play. She tells us that "Mr. Burns emerged from an idea that had been knocking around in" her "head for years". She'd been interested in wanting "to take a pop-culture narrative and see what it meant and how it changed after the fall of civilization". What she realized is how her initial concept had its origins in the fallout of 9/11, when everyone was "thinking about things in a very drastic way. As I was pondering the end of civilization, I imagined that in the midst of a catastrophe, people would tell stories if they had down time. I was interested in which stories would be told, how they would be told, what media makes the transition from the visual to the spoken, and how these stories mutate. We are used to telling stories about things we've seen and books we've read, and in the context of an apocalypse, people would be most interested in something everyone would have in common, so that's where the idea of basing the play on a TV show came from".As she continued to ponder the idea of whether or not stories can or do mutate over the course of time, Washburn appears to admit to having looked into the "trajectory" of other narratives. The closest pure example she could find of this idea was in the case of characters like Batman. At the same time, it's like there's this undercurrent conflict at the heart the author's idea. She can't seem to help noticing an interesting fact about the current state of storytelling. Namely, that some ideas prove more malleable than others. You can shift and change a property like The Simpsons a lot easier than you can a work Anna Karenina. If you tried to do the same thing with the Tolstoy novel, you'd just wind up turning it into something else, and therefore ruining the integrity of initial creative idea. Also, there is the previous observation of S.E. Wolf cited earlier. The concern that "the Simpsons are no longer The Simpsons". Wolf's thinking is that some sort of vital artistic identity has been lost at some point down the road. Washburn and Wolf seem to be juggling two diametrically opposite ideas, and yet my own thinking is that if you put the two pieces of thought together, they help to form a greater whole.

In fact, I almost want to make the claim that Washburn's play helps answer Wolf's concerns about artistic integrity. I'll get to that in a minute, however. Right now, the important thing to note is how Washburn's main conceit plays into the idea of the power and endurance of stories. In her interview, she notes how basing an entire play around The Simpsons, strange as it may sound, "is a good thing to have hit upon, consciously or not. Because the characters are eternal and because its a cartoon, you have such a wide range of stories to choose from. And the characters are archetypal. Bart Simpson is a trickster, similar to mythical characters like Coyote or Kokopelli. He always gets into trouble and always ends up surviving. His heart is in the right place, but he's pure mayhem. And Homer is the idiot, the holy fool. Because the play takes place right after the apocalypse and The Simpsons is about a family, I thought the survivors would care more". I'll admit it's difficult to find anything much that could be called "sacred" in a figure like Homer, even at the best of times. However, it could be that my judgment on the issue is clouded by the recent incarnation of of him. It's a portrayal that, as yet another YouTuber has pointed out, robs the character of any possible artistic dignity that he started out with.

Looked at from this perspective, perhaps its not too far out to claim that Washburn has done both fans in general, and maybe even the character in particular, a kind of genuine favor by returning him to his archetypal roots. For it's true enough that the patriarch of the Simpsons household got his start as a modern riff on a very ancient trope, or topos. This is something that Washburn appears to be aware of on some level, as the play begins to either dissolve or return its characters to their most basic origin points. It's also here that a perhaps underappreciated aspect of the play presents itself. It's in the way the playwright draws all of the familiar personalities from the show in the third act. Not only is her re-fashioning of the main cast a good example of literary excavation presented seamlessly within a straightforward dramatic context. It's also somewhat unique for the way in which it hints at much older traditions of both stagecraft, and perhaps even of writing itself. These are once common tropes that are now perhaps a lot less familiar to a modern audience. Yet these older literary customs have still managed to carry on, even in highly disguised forms to this very day. Once again, Washburn's writing seems to display a keen awareness of these pre-modern ideas, as her own comments are able to show."I was also thinking a lot about Greek drama because it was created by a society that was still deep in trauma over the fall of Athenian democracy, which was the height of civilization at the time". It's this awareness which is put on prominent display by the time the play reaches act three. What the writer has given the audience amounts to a careful demonstration of the historical layers, or strata, of dramatic storytelling. It begins with purely modern, contemporary techniques in the opening act. By the opening of the second stave, the subtle shift has begun to occur as memories blur, and the first hints of archaism begins to creep back into the realm of the arts. We're beginning to see the conventions of what might be termed the "natural" drama existing side by with more symbolic modes of artistic expression. When we reach act three, all naturalism has been tossed aside, and we're in a medium of pure symbolism, where everything about the fiction has been allowed this heightened quality.

It's a dramatic choice that seems to be both deliberate and unconscious on the author's part, and it manages to work like a well played game of cards. The writing is of such a quality that we in the audience barely even notice the subtle transitions taking place right in front of our eyes. By the time the story jettisons the naturalism of of the first half and fully embraces the fantastical allegory of the the last one, the reader may be caught off guard, yet they are never taken out of the experience. Instead, the card trick is played with just right amount of skill necessary to make the switch-over from real to symbolic. In just two easy, yet very difficult to pull off steps, Washburn has transferred us from the world of Anton Chekhov to a realm that bears more in common with the Elizabethan Globe Theater, or the Parthenon, than it does to anything else in recent memory. If fact, if I had to give a concise summary of what this play is really about, then I'd have to sum it up in a phrase like: "The Power of Memory".

I started out this article trying to recall all I could about my history with The Simpsons. While my recollections weren't inaccurate, they were patchwork and sketchy, needing time to dredge themselves up from whatever sort of imperfect storehouse we keep lodged in our heads. Because of this I was able to assemble a very piecemeal recall of what I, personally, have known about the show. The results may have been serviceable, yet they also took time. Nor can they in anyway be described as complete. Incredible as it may sound, Washburn's play seems to have a preoccupation with such moments of half-finished remembrance at its very core. It's a story about stories in terms of both how we tell and recollect them. This added element of memory also means that Mr. Burns qualifies as a metafiction with an interest in the history of stories and storytelling. For better or worse, this makes it kind of a natural subject matter for a site like this, where one of the over-arching focuses is on the historical highs and lows of our favorite narratives, with a particular interest in how and why some stories achieve an all-time, worldwide fame, while others fall through the cracks. A corollary concern is to ask the question of what might happen if a well-beloved book, such as Lord of the Rings, or any other classics you can name start make their way into the dustbins of literary history? What could bring that about?What would have to happen in order for a book like To Kill a Mockingbird, films like Citizen Kane and Casablanca, or a TV show like The Simpsons to reach a level that's so out of favor that history more or less swallows them all but whole, leaving just a few faint trace memories of them behind? While it's a mistake to claim that Washburn's play takes things as far as I've just suggested, it's perhaps true enough that very similar questions were knocking around in the writer's mind as she composed this particular surprise out of left field. It's the kind of subject matter that's sure to get my attention, if no one else's. In the end, Washburn seems to suggest that stories, real stories, the one's with staying power in them, will never quite go away, no matter how much others may try to make it so. This in itself is a rather simple statement to make, and perhaps it sounds like a cliche. What keeps it from degenerating to such a level is two things. The first is that even cliches can have their place, especially if there is a kernel of truth to it, and that thankfully seems to be the case with good stories in general. In particular, however, Washburn's play does a very good job demonstrating the truth behind the statement. Her play winds up as an illustration of the way that stories can survive and thrive long past their initial moment of time.

The final act of her stage story does this on multiple levels. In terms of the surface plot, the actions and stage direction alone contain subtle hints that after a long period of time and travail, the characters within the play world have finally begun to re-build civilization as we know it. This is demonstrated in a clever short-hand fashion. All it requires is nothing more than to close out with an image of a play-actor generating the first real use of electricity in over 82 years with nothing more than a simple exercise bicycle. It has to be one of the simplest, yet surprisingly effective statements of the human capacity for bettering itself, or rising above the level of savage barbarism that I recall seeing in a very long time. At the thematic level, what the play hints at is that it is the human ability to both remember and create art that winds up playing a crucial role in not just giving humans the will to survive, but also to reach higher and strive for better lives for themselves and others. At the core of this play, in other words, is a fundamental belief in the power of stories to both heal and guide in troubled times.

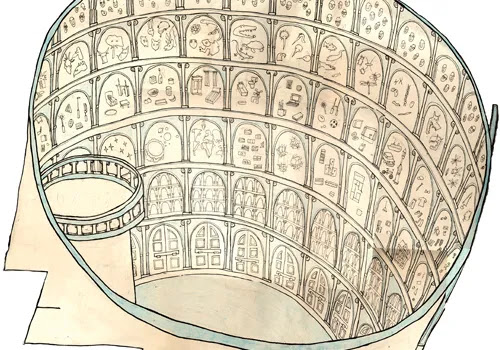

In setting out this basic thesis, Washburn seems to be utilizing yet another aspect of Elizabethan stagecraft. This is perhaps the most speculative part of the review, however I can't help wondering if the author is at all familiar with a Renaissance derived concept known as "The Art of Memory". "Originally developed as a way for ancient Greek and Roman orators to remember their speeches, the art of memory enjoyed a long and varied history. As intellectual historians such as Frances Yates and Mary Carruthers have shown, the art of memory or ars memorativa tradition spread from classical Greece and Italy to the rest of Europe, gained traction in the Middle Ages, and to a wide variety of forms during the Renaissance. Among the oldest and the most popular of these mnemonic methods was the system of loci ("places") and figures (Amanda Watson, 344)". To tell it in plain English, all that phrase amounts is a fancy title for the use of mnemonic techniques, or memory devices that people have been using ever since (and maybe even long before) the Greco-Roman period in order to help them remember any and all useful or important information. What's notable about this simple, psychological exercise in terms of Washburn's story is that the play seems to be reaching back toward a specific usage that mnemonics enjoyed within and during the height of the Renaissance Drama."During the Renaissance, the arts of memory had connections with the theater as well: inventors of memory systems recommended architectural mnemonics resembling stage sets, which were sometimes called "memory theaters". The Italian author Giulio Camillio not only developed an amphitheater-shaped memory theater but built an elaborate wooden model of it filled with images. The idea of the stage as a model for architectural mnemonics reached England during the sixteenth century. John Willis, author of a seventeenth-century memory treatise entitled Mnemonica, includes a diagram of a model back ground or "repository," which resembles an empty stage (ibid, 345-36)". This aspect of Renaissance stagecraft has not escaped notice in the field of "Bard Studies", even going so far as to have an entire book dedicated to the subject in Lina Wilder's Shakespeare's Memory Theatre. It's there that the critic contends "The materials of theatre are, for Shakespeare, the materials of memory'. Shakespeare's theatre is regarded as a 'remembrance environment' where all of the physical and social properties of the theatre, including the props, the players and the physical space of the stage itself are the materials for a mnemonic dramaturgy contributing to mnemonic instruction and recollection (1)".

I bring all of this up because there are moments where it seems as if certain aspects of Washburn's play script act as callbacks to such esoteric Elizabethan literary traditions. For instance, one of the stage directions in her script notes that some of the props, and even some of the gestures made by the performers during the finale are not meant as just in-show callbacks. Instead, it winds up being one of most quiet, yet somewhat heart-warming moments that I've ever noted in a Springfield related project. It's like an item on the play's TV Tropes page says. "We never find out what happened to the survivors, but little things like Jenny's notebook, the forehead touch, and the specific use of Gibson's Gilbert and Sullivan song give the distinct sense that the play is tied directly into their legacy - not just the general legacy of humanity (web)". With all due respect, that's a level of thematic allusion with a greater sense of depth than I think I've ever gotten out so much as a single episode of the entire, original TV show.

It's yet a further testament to Washburn's talent, and the narrative skill that she is able to either layer into, or else uncover as she digs for wherever her story lies buried. All of which is to say, in case you can't tell: I really came away liking this one. This was one of those out-of-left-field ideas that can sneak up on you when you aren't looking. It's not something expected to ever exist, let alone an idea anyone would have. In fact, I wouldn't be all that surprised if part of what helped me ease into the whole idea of Washburn's play was S.E. Wolf's entertaining examination of Simpsons fan culture. In that sense, I was lucky in having the ground prepared for me ahead of schedule. This is not the same as calling the play bad, however. It's possible to have a few critiques, here and there. The biggest complaint I think anyone is ever going to have centers around whether or not the second act tends to drag a bit? Washburn herself explains the logic of what almost feels like an interlude in the main subject matter. Of how she uses it to try and give the audience a sense of the nature of this changed, post-nuclear landscape. It makes sense both on paper and in context. Though I can see a few in the audience complaining that it's a case of world-building at the expense of pacing and narrative momentum.

However, these seem more like nitpicks, than anything else. I can't really find anything wrong with any of the three plot points in the story. For the type of format it's working with, it seems as if Washburn has done all she could, and it turned out to be enough for what the narrative has to tell. What that amounts to is a very clever riff on pop culture and the post-apocalyptic genre. It starts out with a scenario that seems so familiar at this point that its in danger of being done to death, and then takes things in a direction you don't really see coming. From there, you're introduced to an idea that seems so obtuse that you can't really see any way that it could work. Then you either read or see the final product, and the quality of the writing isn't just stunning, it kind of leaves you with a lot to think about in the best sense of the phrase. For me, what the play succeeds at doing is two things. On the first, and most important level, it turns out to be a winning surprise. The story wins you over through it's quirky nature, and a premise that is both screwy and surprisingly touching and humanistic by turns.On another level, the same one that S.E. Wolf talks about, it's almost as if both story and writer have done all the current and former Springfield fans an unintentional, yet genuine favor. If you want an idea of just how impressed I am with this play, then here it goes. I almost wonder if Washburn hasn't come about as close as anyone ever will towards writing a satisfying conclusion to the series as a whole? I know how that sounds, and I'm ready for people to disagree with me on this. However, considering all the lows to which the actual property has sunk to, this play can't help but seem like a satirical jab at how off things have gotten, a loving tribute to glories of the best seasons past, and also something like an epic ode which helps brings everything to a close, while managing to somehow return the main cast to the original archetypes out of which they originally emerged from. I don't have a clue how strange all of that must sound, yet I'll swear its what you'll get if you decide to look into this remarkable offering of off-beat fun. Which just leaves us with one final caveat to be kept in mind.

I've just spent this entire essay singing Washburn's praises. I don't retract any of it, though I do remain aware of the hurdles a story like this will perhaps always have to face. This is no longer a criticism, merely an acknowledgement that when it comes to audiences, the majority taste rules. What that means in this case is that there's always going to be the possibility that a story such as this deserves more acclaim than it will ever be able to get. I spoke just a moment ago of how this play could work as a good series finale. I'm willing to argue its something that could work, especially if you got all of the original cast in on the venture. I'm just not sure a narrative like this will ever have enough mainstream appeal in order to get such a project off the ground. I have spoken of the story as quirky, and that's just what it is. It has all the right artistic charms. It's just that these are strengths that I think crowds are going to have to grow into over a long stretch of time. It's a success that I don't think will be a mainstream favorite. At least that's the not the kind of achievement you can expect it to win anytime soon. That's still no reason for not putting in a good word out there when you can. That's why I think it's important to bring a play like this to the attention of as many out their in the aisles as will listen.

Critic Jonathan Spence once said something interesting about the Art of Memory. "The real purpose of all these mental constructs was to provide storage spaces for the myriad concepts that make up the sum of our human knowledge (2)". I think that's what Ann Washburn has done with a play like Mr. Burns. The writer has constructed a kind of literary memory palace. One that's made up of our accumulated enthusiasms for The Simpsons, pop culture, a few of our darker fears, along with a collective hope that humanity is a thing that can never stay down and out for long, and that sooner or later, some of us will always try to reach for whatever light we can find in the darkness, and that stories are one of the key things that will always be there to help us along. That's why I give this play a high recommendation.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment