"Entertain conjecture of a time". I'm thinking of a pre-digital era, here. Back when the very notion of the Internet was something that didn't even occur to the vast majority of Science Fiction authors of the period. We're talking about a period of transition. The last fleeting moments of the Analog Age. The advent of the modern home computer hasn't occurred yet, though it is just on the horizon. While nerds like Steve Jobs and Bill Gates are busy are hanging around in their parent's garages and futzing with a series of circuit boards that one of them insists on calling an Apple for some reason, the Fantastic genres, like much of everything else is undergoing its own form of aesthetic metamorphosis. The computer hasn't begun to reshape the social landscape just yet. However writers like William Gibson are beginning to craft the first efforts in what will one day become the nascent sub-genre known as Cyberpunk. At the same time, we're talking about a period of history that is so specific, that it would have been possible for small, independent publishers dedicated to selling titles aimed at niche market readers to somehow survive, and maybe even thrive for a time on nothing more than hard work, and with no social network other than the old fashioned word-of-mouth, fanzines, and above all, a lot of good reading material that could be churned out on a reasonable schedule. This was something that could only have succeeded in a time before the era of conglomeration.

Nowadays, the only way the kind of publishing feat I'm thinking of here could ever work would be as an Indiegogo project that is largely self-funded through anyone generous enough to to send in the donations necessary to keep such a digital ship afloat. Back then, however, while a lot of the basics of indie publishing might be considered similar enough to how things are today, there was still enough of a difference to classify those first furtive efforts at creating a popular niche for the lovers of Sci-Fi fiction as to qualify it all as the work of not just another time, or life, but rather that of another world. From what I'm able to tell, even as far back as Medieval times, there have always been a handful of geeks and nerds who were willing to make themselves known. I think the truth of this statement can be born out from what little I recall of a brief snippet of text from an otherwise forgotten critical study by English philosopher and historian R.G. Collingwood. In his academic work, The Philosophy of Enchantment, Collingwood details how the listening audience of the older, oral storytelling traditions (which is all any of us ever had to live with, because books and writing were just a dream, or else some kind of magic) would sometimes wind up in debates with one another over which narrative account given should count as the true form of the tale. The fact that this debate has been around before the proper advent of print and the making of books says at least something about the constancy of human nature.

This seems to hold true no matter what time period you're from. It's just one of those observations that can be both vexing and comforting all in one. How this applies to the creation of fandoms, and how those cultures can sometimes go on to both shape and define the nature of their favorite stories can be demonstrated with two important flashpoints in the history of the popular genres. Both cases amount to no more than the process of fan enthusiasm reaching such a boiling point that the very joy excited by reading your favorite story is enough to make the desire to see those tales collected in a book a reality. The first time this happened was way back in 1937, with the passing of H.P. Lovecraft. At the time of his death, the creator of the Cthulhu Mythos had gone as close to coming out of the shell of his neurotic mindset as he was ever likely to do. For the first and last time in his life, the troubled Mr. Philips had managed to garner a wide circle of friends made up of authors and fellow admirers. It was a series of friendships cultivated through letter correspondence for the most part, yet some of them were lucky enough to meet the Necronomicon scribe in person. With the sudden passing of their idol due to a short life full of long years of ill-health, the Lovecraft Circle was devastated at their inspiration's passing.

The rest is very much as Leon Nielson details it in his Arkham House Books: A Collector's Guide. "After three months of mourning, August Derleth and a colleague, Donald Wandrei (one of Lovecraft's "grandchildren"), made plan to collect and attempt the publication of a memorial volume of Lovecraft's best weird fiction. The idea was encouraged by J. Vernon Shea (another "Lovecraft grandchild"). While many of Lovecraft's stories had been published in pulp magazines, such as Weird Tales, only two books and a few pamphlets had been published prior to his death. Lovecraft's will, however, named a Robert H. Barlow as the executor of the estate, and Barlow had his own plans to publish Lovecraft's stories. This idea didn't sit well with Derleth, and with his considerable faculty of persuasion, he managed to talk Barlow into turning the project over to him...After carefully selecting the stories for the Lovecraft memorial volume, Derleth and Wandrei submitted a manuscript titled The Outsider and Others to two of the larger publishers in New York. Rejections were not long in coming for both of them.

"This discouraging turn of events was only a temporary setback to Derleth. With the support of Barlow...and backed by a bank loan originally secured for building a house, Derleth and Wandrei decided to publish the book themselves. The name of the new publishing venture was derived from the fictitious community of Arkham, which was Lovecraft's place name for Sale, Massachusetts, a setting that figured prominently in many of his stories. In late 1939, more than two years after Lovecraft's death, 1,268 copies of

The Outside and Others with cover art by Virgil Finlay (another Lovecraft devotee) were delivered to Derleth by the printer, the George Banta Company of Menasha, Wisconsin. The cover price of the book was $5.00, a fair amount of money at the time, and it took four years to sell only one printing.

"In spite of the disheartening slowness of their first sales, Derleth and Wandrei felt encouraged to continue the Arkham House imprint and followed in 1941 with a collection of Derleth's own weird tales, titled

Someone in the Dark. The third volume in the Arkham House saga was Clark Ashton Smith's

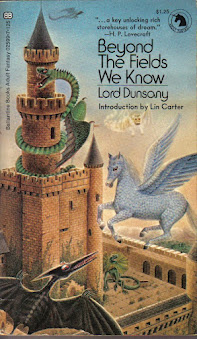

Out of Space and Time, published in 1942. At this time Donald Wandrei had entered the army, and he stayed in the service until the end of World War II. In the years that followed, Arkham House published the works of many of the foremost American and British writers of weird fiction, including Cynthia Asquith, Basil Copper, Lord Dunsany...Frank Belknap Long, Brian Lumley, Seabury Quinn, and Lucius Shepard. In addition, Arkham House also published the first (books, sic) of several notable writers, including Robert Bloch,...Joseph Payne Brennan, J. Ramsey Campbell, Frederick S. Durbin, and A,E, van Vogt (10-12)". When it comes to the legacy left behind by guys like Derleth, we're in somewhat edgy territory. He's the kind of guy who somehow manages to draw controversy for himself whenever he's mentioned in most fan communities, especially any and all centered around Lovecraft.

He's nowhere near as controversial as the troubled artist from Providence. Instead, most of the flak he gets stems from whether or not he was the best thing that ever happened to HPL's reputation. To which I answer some writers are their own worst enemy, and Lovecraft was one of them. Never doubt that. Whatever his strengths as a writer, in a lot of ways, he failed as a human being. I don't see how you need anyone else, especially not Derleth to muddy those waters. Still, to hear the harshest critics tell it, the man responsible for giving the Cthulhu Mythos it's name was little more than a con artist. The kind of guy who, in another life, would have been found running a card shark scam off the pier at Coney Island. A good sampling of this type of opinion can be found here. For my own part, I can't commit to any such rush to judgment. Don't ask me silly questions. I'll play no silly games. I'm just a simple fanboy, and I'll always be the same. It's like Simple Simon said to the Pie Salesman, "Just show me the gosh-damn wears, first. Okay, man? Then I'll decide". From what I can gather, I'm able throw Derleth at least this much of a bone. Some of his work might show glimmers of talent, yet he struggles to bring such creative capabilities to anything like their full measure. His legacy doesn't lie in writing fiction.

Instead, what I don't see how anyone can deny (and here even the detractors tend to give a little ground on the subject; a modicum, at least) is that Derleth really does seem to have been the one who kept Lovecraft's name or works from sinking into the depth of obscurity. If it hadn't been for him, the Cyclopean city of R'leyh would have remained forever sunk, and the Plains of Leng would have gone unexplored. For better or worse, Derleth was the one who first recognized, then hoarded, then did a remarkable job of sharing a veritable treasure trove. It was never an uncomplicated discovery, by any means. It's also (again, for better or worse) one of many writings that helped to pioneer the modern voice of the American Gothic. Derleth was also responsible for at least one other thing, and it's here that we begin to make our way back to subject of this article. It's a mistake to claim that Derleth is the one who created the idea of the fan run and oriented Specialty Press. Guys like Uncle Forry Ackerman and his friends in what is now known as the

Los Angeles Science Fantasy Society beat the founder of Arkham House by at least a year or two when he helped establish

Futuria Fantasia. That seems to have been the first major press dedicated to the stories, poetry, and critical essays by and for the fans.

At the same time, it does seem as if Derleth's venture is the one that has managed to outshine Ackerman's claim to fame. Whether that's good or bad, it is the self-made publishing house that Derleth forged out of an unquenchable liking for the fiction of Lovecraft which seems to have gone on to cast the largest shadow. I think the exact nature of his legacy was summed up long ago by Stephen King, in the pages of

Danse Macabre. "A word about Arkham House. There is probably no dedicated fantasy fan

in America who doesn’t have at least one of those distinctive black-bound

volumes upon his or her shelf... and probably in a high place of honor. August

Derleth, the founder of this small Wisconsin-based publishing house, was a

rather uninspired novelist of the Sinclair Lewis school and an editor of pure

genius: Arkham was first to publish H. P. Lovecraft, Ray Bradbury, Ramsey

Campbell, and Robert Bloch in book form...and these are only a few of

Derleth’s legion. He published his books in limited editions ranging from five

hundred to four thousand copies, and some of them—Lovecraft’s Beyond the

Wall of Sleep and Bradbury’s Dark Carnival, for instance—are now highly

sought-after collectors’ items (266)". In other words, it was guys like Derleth, Barlow, and Wandrei who were responsible for the type of small, independent press capable of giving a voice and outlet for the community of fans.

The efforts of groups like Ackerman and the Los Angeles Science Fantasy Society, or Derleth with Arkham House appear to have been two of the major catalysts that helped spark one of the most unremarked about revolutions in the history of the Fantastic genres. By giving not just a venue, but also an economic outlet for the enthusiasts turned artists and practitioners in the realms of Science Fiction, Sword and Sorcery, and Horror, it isn't just that they were the ones to establish the modern idea of fandom and fan communities as we now know them. It's that they helped pioneer the sense that belonging to a fan culture could be marketable in a way that would force first the business world to take notice, and later lead to the birth of pop culture as we still think of it here and now. The most notable thing about all this is how little attention was paid to this quasi-underground artistic movement. It stands as a testament to just how unimportant the rest of the world thought all this was, that even when Science Fiction began to achieve marquee value in Hollywood during the 1950s, the vast majority of the world was content to write it all off as schlock, and no one ever bothered to think it was just the most visible expression of a coming shift and change in audience expectations and generic tastes.

Even when the idea of the Fantastic more or less took over as the dominant, reigning paradigm of entertainment, it still left the surprised majority of faces in the aisles wondering how this could all have happened? So far as they were concerned, it all came about without them having any sort of clue what was going on. To their credit, a lot of them began going back to take a look at the history of entertainment, and as they did so, with more diligence in the attention they paid to the emerging trends that would metamorphose into pop culture, the easier it became to see how the popular genres began to gain the leading hold over the hearts and minds of readers and movie-goers. What started out as an unprecedented turn of events has now reached the level of acceptance as to be considered a fait acompli. The irony here is that even with this newfound acceptance, there is still a lot of history to this emergence that remains in danger of getting lost in the shuffle, and that's what might happen to the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series of mass market paperbacks, unless a greater degree of attention is brought to this line of publications. There's still a lot of light left to shine on it's achievements.