Nowadays, the only way the kind of publishing feat I'm thinking of here could ever work would be as an Indiegogo project that is largely self-funded through anyone generous enough to to send in the donations necessary to keep such a digital ship afloat. Back then, however, while a lot of the basics of indie publishing might be considered similar enough to how things are today, there was still enough of a difference to classify those first furtive efforts at creating a popular niche for the lovers of Sci-Fi fiction as to qualify it all as the work of not just another time, or life, but rather that of another world. From what I'm able to tell, even as far back as Medieval times, there have always been a handful of geeks and nerds who were willing to make themselves known. I think the truth of this statement can be born out from what little I recall of a brief snippet of text from an otherwise forgotten critical study by English philosopher and historian R.G. Collingwood. In his academic work, The Philosophy of Enchantment, Collingwood details how the listening audience of the older, oral storytelling traditions (which is all any of us ever had to live with, because books and writing were just a dream, or else some kind of magic) would sometimes wind up in debates with one another over which narrative account given should count as the true form of the tale. The fact that this debate has been around before the proper advent of print and the making of books says at least something about the constancy of human nature.

This seems to hold true no matter what time period you're from. It's just one of those observations that can be both vexing and comforting all in one. How this applies to the creation of fandoms, and how those cultures can sometimes go on to both shape and define the nature of their favorite stories can be demonstrated with two important flashpoints in the history of the popular genres. Both cases amount to no more than the process of fan enthusiasm reaching such a boiling point that the very joy excited by reading your favorite story is enough to make the desire to see those tales collected in a book a reality. The first time this happened was way back in 1937, with the passing of H.P. Lovecraft. At the time of his death, the creator of the Cthulhu Mythos had gone as close to coming out of the shell of his neurotic mindset as he was ever likely to do. For the first and last time in his life, the troubled Mr. Philips had managed to garner a wide circle of friends made up of authors and fellow admirers. It was a series of friendships cultivated through letter correspondence for the most part, yet some of them were lucky enough to meet the Necronomicon scribe in person. With the sudden passing of their idol due to a short life full of long years of ill-health, the Lovecraft Circle was devastated at their inspiration's passing.The rest is very much as Leon Nielson details it in his Arkham House Books: A Collector's Guide. "After three months of mourning, August Derleth and a colleague, Donald Wandrei (one of Lovecraft's "grandchildren"), made plan to collect and attempt the publication of a memorial volume of Lovecraft's best weird fiction. The idea was encouraged by J. Vernon Shea (another "Lovecraft grandchild"). While many of Lovecraft's stories had been published in pulp magazines, such as Weird Tales, only two books and a few pamphlets had been published prior to his death. Lovecraft's will, however, named a Robert H. Barlow as the executor of the estate, and Barlow had his own plans to publish Lovecraft's stories. This idea didn't sit well with Derleth, and with his considerable faculty of persuasion, he managed to talk Barlow into turning the project over to him...After carefully selecting the stories for the Lovecraft memorial volume, Derleth and Wandrei submitted a manuscript titled The Outsider and Others to two of the larger publishers in New York. Rejections were not long in coming for both of them.

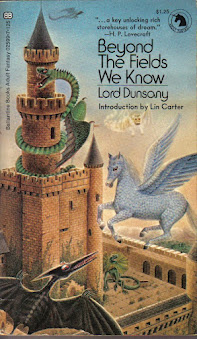

"This discouraging turn of events was only a temporary setback to Derleth. With the support of Barlow...and backed by a bank loan originally secured for building a house, Derleth and Wandrei decided to publish the book themselves. The name of the new publishing venture was derived from the fictitious community of Arkham, which was Lovecraft's place name for Sale, Massachusetts, a setting that figured prominently in many of his stories. In late 1939, more than two years after Lovecraft's death, 1,268 copies of The Outside and Others with cover art by Virgil Finlay (another Lovecraft devotee) were delivered to Derleth by the printer, the George Banta Company of Menasha, Wisconsin. The cover price of the book was $5.00, a fair amount of money at the time, and it took four years to sell only one printing. "In spite of the disheartening slowness of their first sales, Derleth and Wandrei felt encouraged to continue the Arkham House imprint and followed in 1941 with a collection of Derleth's own weird tales, titled Someone in the Dark. The third volume in the Arkham House saga was Clark Ashton Smith's Out of Space and Time, published in 1942. At this time Donald Wandrei had entered the army, and he stayed in the service until the end of World War II. In the years that followed, Arkham House published the works of many of the foremost American and British writers of weird fiction, including Cynthia Asquith, Basil Copper, Lord Dunsany...Frank Belknap Long, Brian Lumley, Seabury Quinn, and Lucius Shepard. In addition, Arkham House also published the first (books, sic) of several notable writers, including Robert Bloch,...Joseph Payne Brennan, J. Ramsey Campbell, Frederick S. Durbin, and A,E, van Vogt (10-12)". When it comes to the legacy left behind by guys like Derleth, we're in somewhat edgy territory. He's the kind of guy who somehow manages to draw controversy for himself whenever he's mentioned in most fan communities, especially any and all centered around Lovecraft.He's nowhere near as controversial as the troubled artist from Providence. Instead, most of the flak he gets stems from whether or not he was the best thing that ever happened to HPL's reputation. To which I answer some writers are their own worst enemy, and Lovecraft was one of them. Never doubt that. Whatever his strengths as a writer, in a lot of ways, he failed as a human being. I don't see how you need anyone else, especially not Derleth to muddy those waters. Still, to hear the harshest critics tell it, the man responsible for giving the Cthulhu Mythos it's name was little more than a con artist. The kind of guy who, in another life, would have been found running a card shark scam off the pier at Coney Island. A good sampling of this type of opinion can be found here. For my own part, I can't commit to any such rush to judgment. Don't ask me silly questions. I'll play no silly games. I'm just a simple fanboy, and I'll always be the same. It's like Simple Simon said to the Pie Salesman, "Just show me the gosh-damn wears, first. Okay, man? Then I'll decide". From what I can gather, I'm able throw Derleth at least this much of a bone. Some of his work might show glimmers of talent, yet he struggles to bring such creative capabilities to anything like their full measure. His legacy doesn't lie in writing fiction.

Instead, what I don't see how anyone can deny (and here even the detractors tend to give a little ground on the subject; a modicum, at least) is that Derleth really does seem to have been the one who kept Lovecraft's name or works from sinking into the depth of obscurity. If it hadn't been for him, the Cyclopean city of R'leyh would have remained forever sunk, and the Plains of Leng would have gone unexplored. For better or worse, Derleth was the one who first recognized, then hoarded, then did a remarkable job of sharing a veritable treasure trove. It was never an uncomplicated discovery, by any means. It's also (again, for better or worse) one of many writings that helped to pioneer the modern voice of the American Gothic. Derleth was also responsible for at least one other thing, and it's here that we begin to make our way back to subject of this article. It's a mistake to claim that Derleth is the one who created the idea of the fan run and oriented Specialty Press. Guys like Uncle Forry Ackerman and his friends in what is now known as the Los Angeles Science Fantasy Society beat the founder of Arkham House by at least a year or two when he helped establish Futuria Fantasia. That seems to have been the first major press dedicated to the stories, poetry, and critical essays by and for the fans.At the same time, it does seem as if Derleth's venture is the one that has managed to outshine Ackerman's claim to fame. Whether that's good or bad, it is the self-made publishing house that Derleth forged out of an unquenchable liking for the fiction of Lovecraft which seems to have gone on to cast the largest shadow. I think the exact nature of his legacy was summed up long ago by Stephen King, in the pages of Danse Macabre. "A word about Arkham House. There is probably no dedicated fantasy fan in America who doesn’t have at least one of those distinctive black-bound volumes upon his or her shelf... and probably in a high place of honor. August Derleth, the founder of this small Wisconsin-based publishing house, was a rather uninspired novelist of the Sinclair Lewis school and an editor of pure genius: Arkham was first to publish H. P. Lovecraft, Ray Bradbury, Ramsey Campbell, and Robert Bloch in book form...and these are only a few of Derleth’s legion. He published his books in limited editions ranging from five hundred to four thousand copies, and some of them—Lovecraft’s Beyond the Wall of Sleep and Bradbury’s Dark Carnival, for instance—are now highly sought-after collectors’ items (266)". In other words, it was guys like Derleth, Barlow, and Wandrei who were responsible for the type of small, independent press capable of giving a voice and outlet for the community of fans.The efforts of groups like Ackerman and the Los Angeles Science Fantasy Society, or Derleth with Arkham House appear to have been two of the major catalysts that helped spark one of the most unremarked about revolutions in the history of the Fantastic genres. By giving not just a venue, but also an economic outlet for the enthusiasts turned artists and practitioners in the realms of Science Fiction, Sword and Sorcery, and Horror, it isn't just that they were the ones to establish the modern idea of fandom and fan communities as we now know them. It's that they helped pioneer the sense that belonging to a fan culture could be marketable in a way that would force first the business world to take notice, and later lead to the birth of pop culture as we still think of it here and now. The most notable thing about all this is how little attention was paid to this quasi-underground artistic movement. It stands as a testament to just how unimportant the rest of the world thought all this was, that even when Science Fiction began to achieve marquee value in Hollywood during the 1950s, the vast majority of the world was content to write it all off as schlock, and no one ever bothered to think it was just the most visible expression of a coming shift and change in audience expectations and generic tastes.

Even when the idea of the Fantastic more or less took over as the dominant, reigning paradigm of entertainment, it still left the surprised majority of faces in the aisles wondering how this could all have happened? So far as they were concerned, it all came about without them having any sort of clue what was going on. To their credit, a lot of them began going back to take a look at the history of entertainment, and as they did so, with more diligence in the attention they paid to the emerging trends that would metamorphose into pop culture, the easier it became to see how the popular genres began to gain the leading hold over the hearts and minds of readers and movie-goers. What started out as an unprecedented turn of events has now reached the level of acceptance as to be considered a fait acompli. The irony here is that even with this newfound acceptance, there is still a lot of history to this emergence that remains in danger of getting lost in the shuffle, and that's what might happen to the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series of mass market paperbacks, unless a greater degree of attention is brought to this line of publications. There's still a lot of light left to shine on it's achievements.If Ackerman and Arkham House are among the first important steps in the legitimization of Science Fiction and Horror, then the punchline is that it still leaves out the one format of storytelling that helps complete the ensemble. While the genres of galactic exploration and things going bump in the night were gaining a greater spotlight, that still meant no one was paying all that much attention to the realm of once upon a time. The Fantasy genre seems to have been the last popular format to take its place on stage with its two other siblings. Just like with Ackerman and Derleth, it was the enthusiasm of a fan base that helped shape the way it was first collected, then marketed to the mass media. This is where the efforts of Betty and Ian Ballantine and their partner in crime, Lin Carter, come into the picture. They seem to be the ones most responsible for giving the Fantasy format the identity it still has. All I've been able to find out about the Ballantines comes from the New York Times obituary for Betty, and the few scraps of information I was able to glean about her husband through his Wikipedia page. Let the dearth of information on both of them stand as an example of the fragile nature of history itself.

Starting out with Betty's significant other, Ian Ballantine seems to have been blessed with the good luck of being born into one of those families that seem able to pass along this ongoing artistic streak through the generations. He was born on February 15th, 1916, in New York, and his father was a Mr. Edward James. Ballantine's future appears to have been shaped by one important aspect of his family household. His father was not just a sculptor, but was also for a time, an talented actor on the Scottish stage. It meant that the young Ballantine would grow up under a roof in which an emphasis on the possibilities of a career in the Arts was treated as a respectable, even desirable achievement. In practice, this emphasis seems to have implied that the boy grew up in an intellectually nursing and supportive home where his parents encouraged his aesthetic ambitions. In Ballantine's case, this appears to have developed into a taste for literature and the written word. In spite of these artistic leanings, Ballantine decided to take the play-it-safe route, and followed in his father's footsteps in a very roundabout way. After receiving his undergraduate degree from Columbia College, Ian traced his steps back very close, though never quite to his father's home of Scotland. Rather than applying to a place the University of Edinburgh, Ballantine graduated from the London School of Economics.

His Master's Thesis from that time is telling, as it all revolves around the monetary possibilities to be had from the careful marketing and selling of small and affordable copies of printed books. I could be wrong on this, yet from just the look and hint of things, it sounds very much as if here we see Ballantine turning into something of a quiet pioneer. His recommendations for the place of small, almost miniaturized books affordable to the masses sounds very much as if we're witnessing the first suggestion of what would later become known as the Mass Market Paperback, or Pocketbook. The kind that fits in the palm of your hand, or stuck inside your pocket, so that it can be lugged just about anywhere with no hassles. So the reader is free to browse the pages if they like. It could be possible that Ian Ballantine is the one responsible for the advent of this format. If there should by any kind of truth to this surmise, then it's telling how far the literary world's fortunes have fallen when it becomes increasingly hard to get your hands on even one of these neat and compact items. I can recall back to days when Pocketbooks pretty much out-weighed the Hardcover first editions. With the slump in book sales that have emerged in the wake of the 21st century, it's become harder to sustain Ballantine's original blueprint for profitability. It means the prices go up, and so does the size of all the books. It's one of the sadder state of affairs I've seen, as it means that the written word has fallen in value.The New York Times obituary is able to fill in the rest of the gaps in the story from here. "While Ian Ballantine, who died in 1995, was the better known of the publishing duo, Betty Ballantine, who was British, quietly devoted herself to the editorial side. She nurtured authors, edited manuscripts and helped promote certain genres — westerns, mysteries, romance novels and, perhaps most significant, science fiction and fantasy. Her love for that genre, and her knowledge of it, helped put it on the map. “She birthed the science fiction novel,” said Tad Wise, a nephew of Ms. Ballantine’s by marriage. With the help of Frederik Pohl, a science fiction writer, editor and agent, Mr. Wise said, “She sought out the pulp writers of science fiction who were writing for magazines and said she wanted them to write novels, and she would publish them.” In doing so she helped a wave of science fiction and fantasy writers emerge. They included Joanna Russ, author of “The Female Man” (1975), a landmark novel of feminist science fiction, and Samuel R. Delany, whose “Dhalgren” (1975) was one of the best-selling science fiction novels of its time.

"The Ballantines also published paperback fiction by Ray Bradbury, whose books include “The Martian Chronicles” and “Fahrenheit 451”; Arthur C. Clarke, who wrote “2001: A Space Odyssey”; and J.R.R. Tolkien, author of “The Hobbit” and the “Lord of the Rings” trilogy. “Betty was succinct and to the point and had a steely eye and was a respected editor,” Irwyn Applebaum, the former president and publisher of the Bantam Dell Publishing Group, now part of Penguin Random House, said in a telephone interview. “Most people who knew the Ballantines would say that much of the editorial vision and brilliance, from variety to quality, that Bantam and Ballantine were known for were due to Betty,” Mr. Applebaum said. “Ian was the proselytizer for their brand of books, but Betty was the identifier, the nurturer, the editor.”

"Elizabeth Norah Jones was born on Sept. 25, 1919, in Faizabad, India, during British rule on the subcontinent. She was the youngest of four children of Norah and Hubert Arnold Jones. Betty learned to read at 3 by following her father’s finger as he read aloud. At 8 she was sent to school in Mussoorie, in northern India in the foothills of the Himalayas, where the heat was less stifling than at home. When she was 13, the family moved to the British island of Jersey in the English Channel, where she completed high school. She did not attend college; instead she took a job as a bank teller on Jersey, where she met Ian Ballantine, an American. They were married in 1939 and sailed for New York. After building Ballantine, the couple sold the business to Random House in 1974, at which point Mr. Ballantine returned to Bantam in an emeritus status and Ms. Ballantine continued to work with authors, including the pilot Chuck Yeager and the actress Shirley MacLaine. The couple also published art books through their Rufus Publications". The Ballantine's major publishing achievements are as follows.

"Betty and Ian Ballantine established the American division of the paperback house Penguin Books in 1939. They later founded Bantam Books and then Ballantine Books, both of which are now part of Penguin Random House. In those early years the challenge for purveyors of high-quality, inexpensive paperbacks was enormous. At the time, Americans mainly read magazines or took out books from libraries; there were only about 1,500 bookstores in the entire country, according to the Ballantines, who wrote about the origins of their business in The New York Times in 1989. With a $500 wedding dowry from Ms. Ballantine’s father, the couple established Penguin U.S.A. by importing British editions of Penguin paperbacks, starting with “The Invisible Man” by H. G. Wells and “My Man Jeeves” by P. G. Wodehouse. They were not alone in seeing the potential of the paperback market in the United States. Pocket Books had just started publishing quality paperbacks, breaking in with Emily Brontë’s “Wuthering Heights” and James Hilton’s “Lost Horizon.”

"Both companies charged just 25 cents per book, making them easily affordable for people unable or unwilling to pay for hardcover books, which cost $2 to $3 each (about $45 in today’s money). And they overcame the distribution problem by making books available almost everywhere, including in department stores and gas stations and at newsstands and train stations. The paper shortage during World War II put a crimp in the business, but that was temporary. In short order, paperback books were flying off the racks and shelves, with readers able to buy two or three at once and more companies starting to publish them. The Ballantines were making good on Ian Ballantine’s stated goal: “To change the reading habits of America.” They left Penguin in 1945 to start Bantam Books, a reprint house. Having purchased the paperback rights for 20 hardcovers, they issued their first round of titles, which included Mark Twain’s “Life on the Mississippi,” John Steinbeck’s “The Grapes of Wrath” and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby.” They started Ballantine Books in 1952, publishing reprints as well as original works in paperback (web)". So it seems like we're dealing with a pair of genuine trend setters here. It's with the birth of their own publishing house that we enter the true heart of this story.

From here, Jamie Williamson is able to lay out the rest of the major facts in the pages of his non-fiction survey, The Evolution of Fantasy: From Antiquarianism to the Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series. According to that study, this is what happened. "The coalescence of fantasy-that contemporary literary category whose name most readily evokes notions of epic trilogies with mythic settings and characters-into a discrete genre occurred quite recently and abruptly, a direct result of the crossing of a resurgence of interest in Ameri can popular "Sword and Sorcery" in the early 1960s with the massive commercial success of J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, the paperback editions of which had been motivated by the former, in the mid-1960s.

"Previously, there had been no identifiable genre resembling contemporary fantasy, and the work that is now identified as laying the ground work for it ("pregenre" fantasy) appeared largely undifferentiated in widely dispersed areas of the publishing market. In the pulps between the wars, and in American genre book publishing between World War Two and the early 1960s, fantasy by writers like Robert E. Howard, Clark Ashton Smith, Fletcher Pratt, Fritz Leiber, and Jack Vance hovered between science fiction, horror, and action adventure fiction. On the other hand, work by Lord Dunsany, E. R. Eddison, James Branch Cabell, and Tolkien, who found "reputable" literary publishers, was not, in presentation, readily distinguishable from the work of Edith Wharton, D. H. Lawrence, E. M. Forster, and Ernest Hemingway, and it was apt to seem anomalous. Other work was absorbed by that modern catchall "Children's Literature," whether it reflected the authors' intentions (as with C. S. Lewis's Narnia series) or not (as with Kenneth Morris's Book of the Three Dragons). It was a common perception that stories with the elements of content now associated with fantasy were, by their nature, suited especially to children.

"A differentiated genre did emerge quite rapidly on the heels of the Sword and Sorcery revival and Tolkien's great commercial success, however its form and contours most strongly shaped by Ballantine Books and its crucially influential "Adult Fantasy Series" (1969-74). By the early 1980s, fantasy had grown to a full-fledged sibling, rather than an offshoot, of science fiction and horror. By now, it has been around in more or less its present form long enough to be taken for granted. A brief account of the construction of fantasy as a genre, then, is an appropriate place to begin the present discussion.

...

"In 1960, there was no commercial fantasy genre, and when the term was used to designate a literary type, it did not usually connote the kind of material that came to typify the genre when it coalesced, particularly in the Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series (hereafter BAFS). But in the early 1960s, there was a swell of interest in what then became identified as "Sword and Sorcery" or, somewhat less pervasively, "Heroic Fantasy." At the heart of this was reprinted material that had originally appeared in pulp magazines between the 1920s and the early 1940s,1 and occasionally later, or in hardcover book editions from genre publishers.2 Published as, functionally, a subcategory of science fiction, Sword and Sorcery rapidly became very popular. Newly identified and designated, there was not a huge amount of back material for competing publishers3 to draw on, and given the general unmarketability of such work during the preceding decade and before, it is not surprising that few writers were actively producing Sword and Sorcery.4 Demand soon overtook supply.

"In this context, Ace Books science fiction editor Donald Wollheim became interested in Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, which had generated something of a cult following among science fiction fans, though it had been released in hardcover in 1954-56 as a sort of prestige item by literary publishers (Unwin in the United Kingdom, Houghton Mifflin in the United States). The elements it had in common with the Sword and Sorcery that had been appearing were sufficient for Wollheim to suppose it would be popular with aficionados of the new subgenre. Duly described as "a book of sword-and-sorcery that anyone can read with delight and pleasure" on its first-page blurb, Ace Books published their unauthorized paperback edition in early 1965.

"The minor scandal attending the unauthorized status of the Ace Books edition, and its replacement later that year by the revised and authorized Ballantine Books edition, no doubt drew some crucial initial attention to the book, but that can scarcely account for the commercial explosion of the following year or two, which has now sustained itself for five decades. The Lord of the Rings sold quite well to Sword and Sorcery fans, but it also sold quite well to a substantial cross section of the remainder of the reading public, and it became a bona f ide bestseller. The Tolkien craze in fact ballooned into something quite close to the literary equivalent of the then contemporary Beatlemania.

"The result of this was something of a split phenomenon. There can be little doubt that the Tolkien explosion bolstered Sword and Sorcery to some degree and drew new readers to the subgenre who may otherwise have remained unaware of it. But Sword and Sorcery never became some thing that "everyone" was reading, as was the case with The Lord of the Rings, and its core readership remained centered in the audience that had grown up prior to the Tolkien paperbacks. In presentation, there was little to distinguish those Sword and Sorcery releases that followed the Tolkien explosion, through the second half of the 1960s and into the 1970s, and those that had preceded it. So there was Sword and Sorcery, and there was Tolkien.

"Ballantine Books clearly recognized this dichotomy. Not a major player in the Sword and Sorcery market, the firm was eager to strike out in a more Tolkien-specific direction. The initial results over the next few years were a bit halting and haphazard. The Hobbit followed The Lord of the Rings in 1965, and the remaining work by Tolkien then accessible was gathered in The Tolkien Reader (1966) and Smith of Wootton Major and Farmer Giles of Ham (1969). The works of E. R. Eddison, a writer Tolkien had read and enthused on, appeared from 1967 to 1969. The year 1968 saw the less Tolkienian Gormenghast trilogy of Mervyn Peake, as well as A Voyage to Arcturus by David Lindsay. Like The Lord of the Rings, these works were originally released by "reputable" literary publishers. The Last Unicorn, a newer work by young writer Peter S. Beagle published in hardcover by Viking the previous year, appeared in 1969. The more impressionistic cover artwork of these releases served to distinguish them from the Sword and Sorcery releases of Lancer, Pyramid, and Ace: no doubt Ballantine wished to attract Sword and Sorcery readers, but they were also attempting to attract that uniquely Tolkien audience that Sword and Sorcery did not necessarily draw."Enter Lin Carter. A younger writer who had begun to publish Sword and Sorcery, including Conan spin-offs in collaboration with de Camp, during the mid-1960s, Carter approached Betty and Ian Ballantine in 1967 with a proposed book on Tolkien. This was accepted and published as Tolkien: A Look behind the Lord of the Rings in early 1969. One of the chapters, "The Men Who Invented Fantasy;' gave a brief account of the non-pulp fantasy tradition preceding Tolkien, which dovetailed with what Ballantine had been attempting with their editions of Eddison, Peake, Lindsay, and Beagle. Sensing a good source for editorial direction, Ballantine contracted Carter as "Editorial Consultant" for their subsequent Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series, which commenced in spring 1969 (see I Carter 269).

"The importance of the BAFS in the shaping of the fantasy genre cannot be overestimated. It was the first time that fantasy was presented on its own terms as a genre in its own right. Though the volumes were inevitably destined for the science fiction sections in bookstores, the "SF" tag was gone, replaced by the "Adult Fantasy" Unicorn's Head colophon;5 the gar ish, often lurid cover art became softer colored, drifting toward the impressionistic and the surreal; the muscle-bound swordsmen battling ferocious monsters (with the free arm around a scantily clad wench) were replaced by Faerie-ish landscapes. It was also the first time the peculiar cross section of work now considered seminal in the genre was drawn together under a unified rubric; to this day, it stands as the most substantial publishing project devoted to (mainly) pre-Tolkien fantasy. Sheer quantity also lent the BAFS indelible impact. With 66 titles in 68 volumes published between 1969 and 1974 (regularly one and sometimes two a month before a slowdown in late 1972), the BAFS rapidly became the dominant force in fantasy publishing (whether tagged "SF" or not). There was no real competition. The bully pulpit engendered by this dominance gave the BAFS far-reaching influence in two crucial respects."First, it gave the BAFS the power of defining the terrain. In Tolkien: A Look behind the Lord of the Rings, Imaginary Worlds (a study of the newly demarcated fantasy genre published in tandem with the BAFS in 1973 ), and in dozens of introductions to Series titles, Lin Carter repeated an operative definition of what was now simply termed "fantasy": "A fantasy is a book or story ... in which magic really works" and, in its purest form, is "laid in settings completely made up by the author" (I Carter 6-7). Carter further stipulates that fantasy circles around the themes of "quest, adventure, or war" (2Carter ix). Some four decades later, a wildly prolific body of work unambiguously reflects the terms of this template, then newly formulated under the aegis of the BAFS."Second, the quantity of titles, with primary emphasis on reprints, gave to the BAFS the power of determining a general historical canvas and implicitly shaping a "canon" of fantasy. Carter's introduction to the 1969 BAFS edition of William Morris's The Wood beyond the World begins with the portentous declaration: "The book you hold in your hands is the first great fantasy novel ever written: the first of them all; all the others, Dunsany, Eddison, Pratt, Tolkien, Peake, Howard, et al., are successors to this great original" (Carter ix). This basic contention, like the aforementioned definition, was repeated over and over again in Carter's commentaries and books, with Cabell, Clark Ashton Smith, de Camp, Leiber, Vance, and a few others rotating into the list of Morris's followers, depending on which recitation you encountered. The dispersal by author of the BAFS titles suggests how the canon-shaping nature of Carter's declarations were given body. The "major authors" were William Morris (four titles in five volumes), Lord Dunsany (six volumes), James Branch Cabell (six volumes), E. R. Eddison (four volumes), Clark Ashton Smith (four volumes), and Tolkien (six volumes).8 That the relevant work by Howard, Pratt and de Camp, Leiber, and Vance included in the BAFS was minimal in quantity9 reflects the fact that it was already available in editions by Ace, Lancer, and so on at the time, and Ballantine was not interested in issuing competing editions. On the basis of Carter's oft reiterated "list," however, those authors' work should rightly be considered part of the BAFS canon, though little of it actually appeared in Series releases.

"Like the BAFS template, this informal canon has held through the succeeding decades. Despite its massive proportions and the breadth of the permutations of fantasy covered, John Clute and John Grant would declare in the introduction to The Encyclopedia of Fantasy ( 1997) that the late nineteenth- and twentieth-century authors representing "the heart of this enterprise" were "George MacDonald, William Morris, Lewis Car roll, Abraham Merrit, E.R. Eddison, Robert E. Howard, J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt, Fritz Leiber ... and so on" ( Clute and Grant viii). This is, more or less, the Carter/BAFS canon. 10 Since the millennium, no doubt partly spurred by the renewed Tolkien boom following the Peter Jackson films, small publisher Wildside Press has mined the BAFS for titles for its classic fantasy series - even reprinting some Lin Carter introductions. It doesn't always seem to be remembered that this "canon" was functionally constructed by Carter and Ballantine Books three to four decades ago, cobbled together from work of widely disparate publishing backgrounds (1-5)". If it's true that Carter is the one who wound up laying down the initial definitions for what counts as the "canonical" nature of the modern Fantasy genre, then I can't help noticing the remarkable way that the passage of time has in causing these terms and conditions to lose their shape over the years.These days it seems like the nature of the Fantasy genre as a whole seems to boil down to just a handful of names. There's J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Lewis Carroll, Suzanne Collins, Neil Gaiman, J.K. Rowling, and George R.R. Martin. Put that all together and you've got a definition that is similar to the contours established by Carter, and yet there are a lot of differences thrown in their as well. Some are major, and yet others a so minor as to be unnoticeable. That's because it seems for all that Carter and the Ballantines where hoping for, it appears that they've failed in their goals by succeeding in such a way that nobody remembers them anymore. Their biggest success seems to rest in helping to put Middle Earth on the map. The complete and total irony is that their partial goal of making Tolkien into the pop culture icon that he is now was such a triumph, that it has led to the total eclipse of both Carter and the Ballantines. Almost everybody and their grandparents know what a Hobbit is. Who on Earth ever heard of (much less has time for) the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series? The perfect irony of history seems to be that in order to get a coherent picture of it, a lot of facts have to be tossed away.That's just one supposition for how the process of codifying the past might work. I hope to God that's not the case. There's too much important information out there that most of us need to help us live complete and ordinary lives, and it could one of those cases where even the merest knowledge about the past could be the difference between life and death. However what can't be denied is this one constant. In almost every summation of the past I've read or watched, there's always a page or two of footage missing. Something is always getting left out. Sometimes its a minor seeming bit of trivia about the motivations of an important figure that leaves our understanding of that person incomplete because we've all missed that one crumb of a person's philosophy. At other times, it's like with Betty and Ian Ballantine, where an entire chapter is missing from the history books because no one ever thought they were important enough to remember. That strikes me as a mistake, even in the best of circumstances.

I don't see why it should be the case that good literary talent has to be forgotten. That's sort of why I've constructed this entire article as an introduction to guys like Lin Carter and the book collection he helped shepherd into a brief yet glorious span of life. Guys like Carter, or women like Betty Ballantine, and others like Forrest J. Ackerman, and August Derleth all have one thing in common. They're the unsung names responsible for us even having the ability to create a community of friends and acquaintances centered around our favorite books and films. I guess what I'm trying to say in all this is that while we will always owe folks like Carter and Betty Ballantine a debt for opening the realm of Middle Earth up to us, it's important to both recognize and remember that they wanted to do so much more. They wanted to give us an idea of the richness that the Fantasy genre was capable of, even beyond the confines of Hobbiton and Mordor. They realized that landscape of Once Upon a Time was a realm with many vistas and sights just as fantastic (if not more so) than what was dreamed of by Tolkien. Some of them, like Lord Dunsany, were part of the Oxford scribe's Cauldron of Story.Carter and the Ballantines felt that was a very important thing to keep in mind. It wasn't just enough for readers to enjoy a story like Lord of the Rings. They wanted fans to know about the kind of stories that helped create places like Mirkwood and the Misty Mountain, and the authors who wrote about them. It might not sound like much, yet it's a sentiment I have to applaud. Because it shows all the signs of readers who take the written works they like seriously. Something like the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series could only have come about as a labor of love. It's the sort of thing that today's bottom line focused market would never allow. It stands as one of the most unremarked upon works of passion and dedication undertaken for the sole reason of the level of enthusiasm that all involved had for the idea, and the type of fiction at the center of it all. I can see this kind of thing happening today. However, it will always be the sort of venture that's confined to the out-of-the-way independent marketing scene. There's just no way that the corporate media environment would ever be able to take a chance on, much less be capable of forming a workable grasp of the kind of fiction Carter was editing for the series.

It just takes a certain type of mindset that, while maybe not getting any more rare, is nonetheless at risk of being sidelined by a homogenized and stifling media ecosystem. Hence the ultimate reason for this article. I had a chance not too long ago to refresh my memory on the nature of the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series. Doing so was best described as one of those helpful wake up calls the critic or reader can get while devoting their time to the artform they love. Moments like that are good at reminding us that all good writing is a matter of standing on the shoulders of giants. It also helps us to recall that the nature and environs of the Fantasy genre is a lot wider than just the confines of Middle Earth. This is something Tolkien himself was eager to highlight. One purpose that the Oxford Professor's essay On Fairy Stories has in common with Carter in his capacity as editor of the Ballantine lineup was to shake readers out of their generic complacency. To take them by the lapels and say, "Hey, listen, there are a whole slew of vast and grand secondary worlds out there within the pages of lost and forgotten volumes that are worth re-discovering, and all of them are still out there, just waiting to be picked up and read.

In fact, one of the most important aspects of the writing and publication of The Lord of the Rings is that it was meant in large (though now mostly forgotten) part as a clarion call, of sorts. It was the author's way of both paying tribute to the works of Fantasy that inspired him, while also (and again, Tolkien's goals here line up very well with Carter and the Ballantines) hoping it would be used as a signpost pointing the way back toward all of books of wonder that he took so much enjoyment out of as just this geeky, awkward fanboy in his own right. Something tells me that Tolkien was able to live long enough to watch with a great deal of regret as his own literary creation took on so much a life of its own that it actually wound up defeating one of his major intended goals. LOTR became so popular as to eclipse any knowledge of writers like William Morris, Lord Dunsany, or George MacDonald. That was never the intention. Tolkien meant to give them all a renewed voice in the modern age. And so he wrote something of such a quality as to erase his inspirations from living memory. I'm pretty sure life is full of little ironies like that. And to his credit, Tolkien seems to have been the kind of guy who could appreciate it. It also doesn't change the fact all of those names and stories were lost to time.The same process even played itself out in miniature with Carter's editing of the Ballantine series. Like Williamson says, the biggest sellers of that entire collection was any and everything Tolkien related, while names like Poul Anderson and Joy Chant more or less languished on the shelf. It's telling that the entire career of the Ballantine Fantasy paperbacks spans out at just four to five years. It's as perfect a snapshot chronicle of the diminishing demand for supply as the tastes of genre fans worldwide begin to shift toward the types of artistic parameters Tolkien outlined in his books. Just like with the Professor, Carter expended hours of sweat and effort trying to wake readers up to the literary value of names like William Hope Hodgson and Evangeline Walton, only for the Land of Mordor to cast an all-consuming shadow over everything related to Sword and Sorcery. I wonder if Carter was ever able to appreciate the irony of what was happening all around him like Tolkien did. Whatever the case, the fact remains that both the Oxford Philologist and the American Publisher Couple and their Editor Friend were all onto one shared great idea. Fantasy is always vaster and greater in scope than what we know.

It's what makes the efforts of Tolkien, Lin Carter, and Betty and Ian Ballantine worth preserving and not just remembering, but also re-discovering for a new era of readers. That's why this article really counts as a kind of advocacy for the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series. It's written in the hope that anyone reading this will be willing to go on from here and try and hunt down the forgotten secondary worlds of names like James Branch Cabell, H. Rider Haggard, L. Sprague De Camp, and Fletcher Pratt. The key thing to keep in mind is all those guys listed are just plain fun to read. It's the most important criterion I can give for enjoying a good book, and they all fulfill it in bucket loads. Each in their own way sort of helps remind readers of all the various paths artists could take in making their stories a plain, fun romp for their readers to enjoy. At the same time, they can help to re-awaken us, not to all the roads not taken, so much as the once common literary byways that have grown old and forgotten with disuse. If the Fantasy genre is in the midst of looking for a good shot in the arm, then maybe that's a clue that it's time for readers and writers to take a cue from Tolkien and Carter by going back to the original well, and discover what overlooked treasure troves might be laying in wait for us at the bottom.

It's with this goal in mind that I hope there may be some out there who are brave enough to read this article to the end. If so, then my fondest wish for this particular piece of doggerel is that once you're done with it, if you're curious enough, then it might not hurt to go out and look up the titles of Betty Ballantine's and Lin Carter's collection of texts. A complete list of the series can be found here. I think I'll leave things off here with a neat video essay summary of the Ballantine Fantasy Library as a whole (see below). There's a lot to explore in a book collection like this. It makes sense enough that a lot of the artists who wound up on the Ballantine list are bound to get their own day in the spotlight here at the Scriblerus Club. It will have to be considered as a simple matter of "All in Good Time". What I can say for now, by way of parting, is this. Of the names in Lin Carter's collection that I have gone through already, I think I can say with some assurity that they are well worth a heart recommendation from me.

No comments:

Post a Comment