"I knew, watching, that the Creature had become my Creature; I had bought it. Even to a seven-year-old, it was not a

terribly convincing Creature. I did not know then it was good

old Ricou Browning, the famed underwater stuntman, in a

molded latex suit, but I surely knew it was some guy in some kind of a monster suit.. .just as I knew that, later on that night,

he would visit me in the black lagoon of my dreams, looking

much more realistic. He might be waiting in the closet when

we got back; he might be standing slumped in the blackness

of the bathroom at the end of the hall, stinking of algae and

swamp rot, all ready for a post-midnight snack of small boy.

Seven isn’t old, but it is old enough to know that you get what

you pay for. You own it, you bought it, it’s yours. It is old

enough to feel the dowser suddenly come alive, grow heavy,

and roll over in your hands, pointing at hidden water (103-4)". It helps to keep in mind that what King is describing here is the emotional reaction, or the Stock Response effect that the last of the classic Universal Monster pictures had on him. The key things to pay attention to in all of that word salad is how the film was able to get its intended effect across in spite of its limitations. King could tell the special effects were nothing to write home about, even in 1954.

At the same time, the final product was of such a quality that it's overall schlocky nature could never really get in the way of the picture's ultimate triumph as a fright flick. It's interesting to note that the author of Carrie is not alone in his reaction. It seems that the Creature has managed to capture the Imaginations of audiences right down to the present moment. It's possible enough to demonstrate at least the veracity of this claim when proof can be offered by the following video review. That word "capture" is worth keeping in mind. Because that's what the good work of Horror does, regardless of production value. It's the reason King is able to say with complete sincerity that "My reaction to the Creature on that night was perhaps the

perfect reaction, the one every writer of horror fiction or director who has worked in the field hopes for when he or she

uncaps a pen or a lens: total emotional involvement, pretty

much undiluted by any real thinking process—and you understand, don’t you, that when it comes to horror movies, the

only thought process really necessary to break the mood is for

a friend to lean over and whisper, “See the zipper running

down his back?”

"I think that only people who have worked in the field for

some time truly understand how fragile this stuff really is, and

what an amazing commitment it imposes on the reader or viewer

of intellect and maturity. When Coleridge spoke of “the suspension of disbelief” in his essay on imaginative poetry, I

believe he knew that disbelief is not like a balloon, which may

be suspended in air with a minimum of effort; it is like a lead

weight, which has to be hoisted with a clean and a jerk and

held up by main force. Disbelief isn’t light; it’s heavy. The

difference in sales between Arthur Hailey and H. P. Lovecraft

may exist because everyone believes in cars and banks, but it

takes a sophisticated and muscular intellectual act to believe,

even for a little while, in Nyarlathotep, the Blind Faceless One,

the Howler in the Night. And whenever I run into someone

who expresses a feeling along the lines of, “I don’t read fantasy

or go to any of those movies; none of it’s real,” I feel a kind

of sympathy. They simply can’t lift the weight of fantasy. The

muscles of the imagination have grown too weak. In this sense, kids are the perfect audience for horror. The

paradox is this: children, who are physically quite weak, lift

the weight of unbelief with ease. They are the jugglers of the

invisible world—a perfectly understandable phenomenon when

you consider the perspective they must view things from (104-105)".

This is a fundamentally Romantic way of looking at the genre and its intended effects. If proof were needed for that statement, all you have to do is go back and see King invoke one of the key maxims of that literary Movement, even going so far as to name drop the handle of Romanticism's primary architect. In King's favor I'll just go ahead here and say that it's easy to prove what Coleridge says about the inherent fragility, perhaps even the innate ridiculous nature of the Gothic. The prime example I would point to is the Shower Scene from Hitchcock's Psycho. We tend to think of it was one of the most iconic and visceral moments in the history of Slasher film. I'm of two minds about this. On the one hand, it's impossible to deny. The entire sequence works as a masterclass in pacing, editing, imagery, and sound. I also can't help being amused at how well people are affected by a scene where, in the strictest sense, no violence is ever committed, and not so much as a single drop of blood is shed.

Go back and look at that sequence again with a more alert eye, and you'll begin to notice all the ways in which ol' Hitch more or less tricks you into doing the dirty work for him. Note for instance that we never really see the knife doing anything that would constitute as an actual attack. It's even possible that the choreography of "Mrs. Bates'" actions are deliberately a bit too slow to leave an impact. Even the pacing of the moment, and the reactions of the characters in the scene count as unrealistic when you reflect on just how stylized everything is. Perhaps the strangest compliment I can give to Hitchcock with this scene is also the greatest sounding, yet it's also the truth. The Master of Suspense was always tasteful enough to never show us an actual crime being committed at any point in his career. Instead, all we've got with the encounter between the unfortunate Janet Leigh and "Mother" is little else except pure thespian histrionics and mugging for the camera. In other words, Coleridge was correct. It really doesn't take much to defuse even the best made examples of Horror. Applying the Romantic Poet's dictum to Hitchcock's most famous movie reveals it to be the cheapest sort of carnival trick. I think this is also what makes it cool as hell. When looked at properly, the Director has to be congratulated here.

It really does count as a prime example of a sleight-of-hand trick well done. That's all Horror or any work of fiction amounts to, in the long run. It's all just a magic act where the zipper on the monster suit is always visible sooner or later. I almost want to say that the inability of all Horror to get away from revealing that zipper on the suit is perhaps the defining trait of Schlock. What happens in practice then is that all Horror cinema comes down to a question. Are you willing to grant the genre it's limitations, whatever they are, and be willing to meet any story in this mode on those terms? It's the sort of question that pretty much every adaptation of a Stephen King story winds up asking of its viewers. Though I'd argue it also holds true for Horror as a whole. For my part, I make no bones about where I stand on the issue. I'll always be more than happy to enter into the Schlocky spirit of things that underlines just about every King movie I've ever seen. I make no apologies for the honest enjoyment I get out of this stuff. It's just plain fun to me. With that said, are there any moments where the ability to enjoy this sort of film comes to an end, and where does The Monkey fit in with this kind of scheme?

The Story.

This is the story of two brothers, Hal and Bill Shelburn. It's also about the discovery they found waiting for them, tucked away in the back of a closet in their parents' house. This is the story of how that discovery re-shaped their lives in ways none of them could have imagined. Hal and Bill are typical of boys next door, in some cases. At the same time, you might say that Tolstoy's line about how unhappy families are all unique in their own way applies to them as well. For one thing, their Dad is no longer any kind of presence in their lives. The boys' father went out one night (for a pack of cigarettes, or at least that's what he told them) and hasn't really been seen since. The funny thing is it's hard to tell if this ever did any kind of number on their mother's outlook on the general nature of things. She's the kind of girl who is prone to saying things like, "Everything is an accident. Or, nothing is an accident. Either way, same thing". Another of her witty observations goes something like: "Christ, what's worse than a blind date. I'd rather take my chances and kiss a goddam frog and see what happens". She's was also the kind of mother who greets her sons with a hearty, "What are you doing in here all alone, Hal...Or do I not want to know"? And on the content of her ex-husband's closet, she was able to declare that, "One day, my darling boys, all of that horseshit will be yours". Unhappy families are unique in their own way. Like I say, though, I can't tell if this is a recent trend, or if they were always like that more or less.

Take Hal's older brother Bill, for instance. According to Hal, "Bill was the kind of kid that would say, "Shake on it", then pull his hand back and pretend to slick his hair. He was older than me by three minutes and ate most of my mom's placenta. So that made him my Big Brother. A role he took seriously, and treated me like shit whenever he got the chance". Example: the two brothers are brushing their teeth, getting ready for school in the morning. Bill turns to Hal and informs him: "I didn't mean to tell you. Mom says she hates you because you made Dad leave and now she has to go on dates". "I managed to love him anyway", Hal insists, "even if I did sometimes fantasize about being an only child". Said fantasies often take the form Hal caving in his brother's face with a metric ton bowling ball, so you be the judge of his words. Anyway, at first Hal is the kind of kid who is willing to just sit there and let his little brother pick on him. Then one day, I guess Hal must have felt kind of nostalgic, because he goes riffling through the junk in his Dad's old closet. It's while trying to recover traces of a lost parent that Hal makes the discovery, tucked away amid his father's expired flying licenses and airline pilot uniforms. It looks like an ordinary hat box, but what's inside isn't a hat. It's a Monkey.

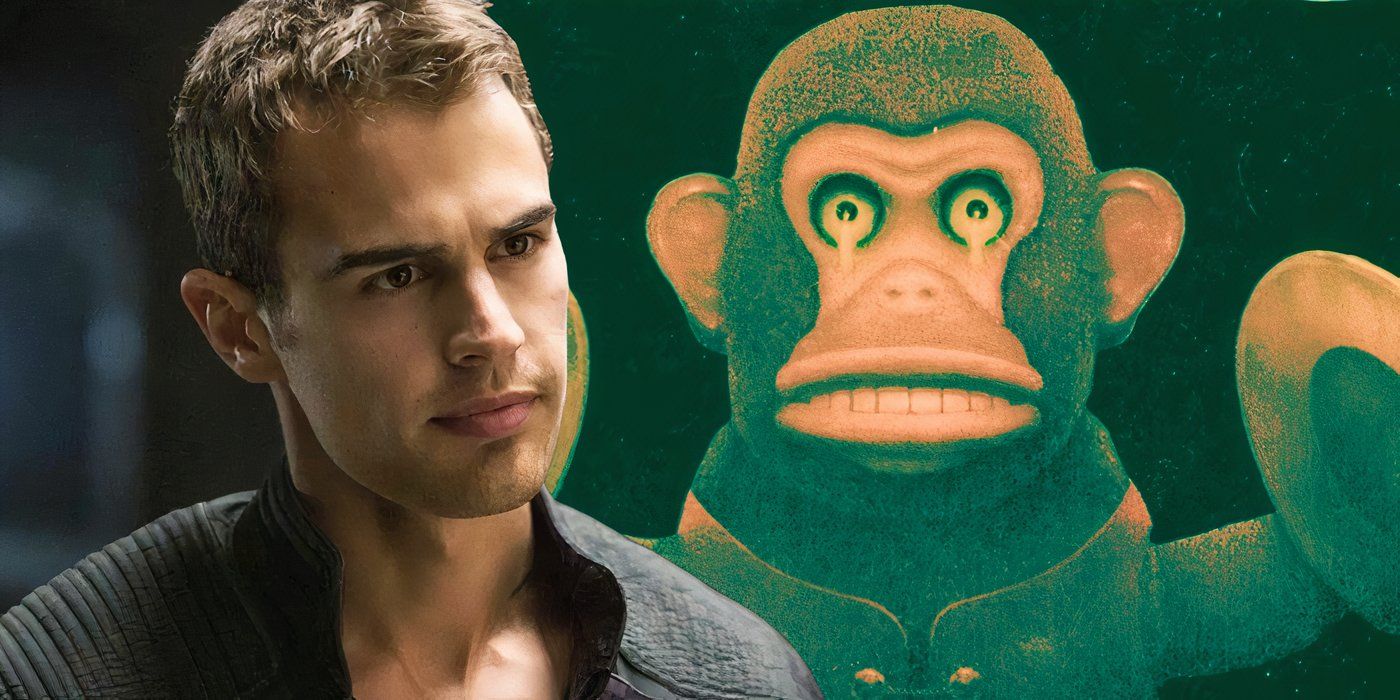

To be specific, it's one of those little wind-up toys, the kind they sell at novelty shops, and that somehow always manage to find their ways into flea markets and basements or attics. One look at this artifact and it's easy to imagine it sharing pride of place up on a shelf as the potential prize in some demented carnival game. The Monkey is about the size of your average Raggedy Ann doll. It's fur is dark brown, dressed in yellow striped pants, and a light red vest. It's built in a sitting position, and on it's lap is a small toy drum. It's arms are constructed in an eternal clenched fist, because that's where the drumsticks are permanently attached. They're fastened to the palms on little cogs that cause them to rotate when the toy is in operation. The most notable feature of the Monkey is it's face. When you see something like that you kind of have to wonder what could have been going through the mind of the original designer when he crafted the darn thing. The overall appearance of the Monkey gives off this vibe of a toy built by someone who isn't quite used to having normal thoughts. Whoever made this contraption was used to having a lot of bad ideas in their head. This is on display in the final product.

The wrinkled, simian facial features wouldn't be all that remarkable except for two things: the mouth and the eyes. For one thing, the mouth is designed to open and close. I didn't know it could do that. When it's not grinning at you I guess it could almost pass for normal. Just another denizen of the animal house, with nothing else to write home about. It's when a switch is flipped, and the mechanism comes alive, allowing those plastic lips to draw back and expose those hungry looking pearly whites that you get your first hint of something wrong. The initial off note is completed when you take the eyes of the Monkey into the equation. I've said whoever designed this thing was used to not having normal thoughts. That becomes perfectly clear when you notice the eyes, and the way they look at you. Perhaps all they amount to is just a pair of carefully manufactured marbles welded into a metal framework. It's not enough to get rid of the look that's in them. You hear a lot of talk about the uncanny valley. How certain artifacts are made in such a way that the overall look and feel of a painting, image, or object can come off as inhabiting that uncomfortable borderland where a thing looks either human or natural enough, except for a handful of touches that can't erase this uncanny artificial quality to it.

It's a phenomenon that's easy to point out. There are perhaps over a million examples of this kind of result out there, and most of them have long since been posted on the web in a kind of digital freakshow collection to be gawked at and wondered over. Most of it involving poor digital animation, and, of course, the curious designs of certain children's dolls. This Monkey was kind of like that. However, in a lot of other ways, it just doesn't compare. As Hal looked into the looked into the blank, wide-eyed gaze of this old, discarded toy, he couldn't shake the feeling that the look it was giving him was one of pure, unbridled, grinning malevolence. This was no cute little organ grinder's mascot. This was one mean, mandril ape. Something with teeth, and one hell of a dangerous temper. It was the sort of toy that looked like it might like to reach and bite you whenever it could. So of course, Hal knew he had to try and see how it worked, right away. Whether you want to call it the allure or fascination of the Uncanny, or else just nature's way of trying to cut out the dross from the herd, Hal started futzing with the damn thing, and pretty soon discovered that you made it work by sticking a key into it's back.

There was no other instruction that Hal could find. Just a sticker posted on the box the Monkey came in that read: "Turn the Key and See what Happens". So he did. At first, nothing happened. Then later on, while the boys were taken out for a Chinese dinner by their baby-sitter because their Mom was on yet another date, the Monkey came to life. The kids were in the restaurant with the sitter when this happened, yet they saw the final results. The Monkey played, the chef serving the kids at their table did his trick with carving the meat and serving it up hot and steaming, and when the toy had finished pounding out its drumbeats, the sitter turned to them and her head fell clean off. The doctor's said the chef at the restaurant wasn't paying attention to what he was doing with his carving blades, and his hands sort of became accidental lethal weapons for a moment there. Oh well, these things happen, or at least that's what you're expected to say, so...Hal, meanwhile, begins to have his suspicions. After a further bit of ghoulish confirmation, coupled with his brother paying off a bunch of girls at school to pretty much beat the living shit out of him, Bill Shelburn's little brother runs up to the room they've shared since they were babies, drags the Monkey out of it's box, makes a very dangerous wish, and turns the key. The Monkey played it's drum, and just like that, everything went straight to hell.

Conclusion: A Marvel of Missed Opportunities.

I almost want to say it'll be easy to leave King out of this review. That's because we're dealing with one of those cases where even if the movie itself is drawn from his work, the final product has almost nothing to do with it's source material. I guess this means I should clarify a few ground rules I've got about book to film adaptations. If you were to ask what it is I look for in translating literature to the screen, then the answer is obvious enough, for the most part. I hope they're able to dramatize the book. It's pretty much the closest I've got to a general approach for how film adaptations should be done. This maxim goes double for those cases when it's obvious the book can't be improved upon. However, with that said, I'm also willing to allow exceptions to this rule. For instance, if we're dealing with one of those cases where the original text leaves a lot or too much room for actual improvement, then I'd argue we're dealing with a story that is fundamentally incomplete, and is still waiting for any artist with the talent necessary to give it whatever finishing touch is needed to allow it a successful run across the finish line. This is something that has happened before, and it's easy to point to a number of such examples.

Let's take, for instances, films like Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, and Who Framed Roger Rabbit. It really is an open question in my mind just how many fans of either flick realize that they both started life as ink and paper novels? It's just possible that a sizeable number of Wonka fans know that the character and his story both emerged from the mind of children's author Roald Dahl, and that it's original name was Charlie and the Chocolate Factory Some of the more die-hard bookworms and cinephiles out there will even be aware of the minor skirmish over whether or not the film does justice to Dahl's fiction. I'll have to admit that these things exist. It's also a fact that the vast majority of the audience probably has next to no idea that any of it does. So far as the average viewer is concerned, what does it matter where a story comes from? It's a mindset that doesn't seem to be perennial, or anything like that. It's just been around for a long enough time that several generations have come and gone to the point where most folks think it has always been this way. There is, however, no inherent reason why this arrangement can't change for the better one day. I'd argue that even if this is the ruling mindset with regard to Art and Storytelling for the moment, it's still a very incorrect vantage point.

Finding where a story comes from, and whether its original format telling, or it's adaptation is the best can be a useful exercise in criticism and analysis. As it enables the audience to learn a great deal about the art that goes into the writing of fiction. It's a necessary yet sometimes overlooked fact that applies to all aspects of narrative creativity, from pacing and action, all the way to characterization and what narrative plot beats can be determined as essential or otherwise. Sometimes turning the book into a film doesn't even qualify as an adaptation, but rather as a form of completion. It's what can happen when the content of a published book turns out to be a very slipshod rough draft in need of further editing and revisions. I'd argue that's what happened in the case of both Wonka and Roger. With all due respect to Dahl fans, the original book is one of those texts that starts out with an intriguing premise, and then sort of begins to peter out one slow bit at a time when the moment comes for the story show the big payoff that's been setup. A good a linear plot winds up as just an episodic mish-mash of set pieces with the merest through-line to string it altogether. On top of that, there are some troubling racial politics what make the original book problematic, and just serves to get in the way of the story when it shouldn't have. The Mel Stuart adaptation, however, is able to address all of these issues in creative ways.

Screenwriter David Seltzer is able to take Dahl's initial concept of a child winning the chance to have his or her dream come true and tighten not just the narrative, but also the thematic focus of the creative idea into a pilgrimage into this otherworldly setting that is able to be both hell, Purgatory, and Paradise all wrapped up together in one. The idea of the entire Chocolate Factory as a one long secret test of character is brought to the fore as it should be, and hence the narrative is given a greater sense of urgency and stakes as we're left to wonder if anyone is capable of living the Imaginative life. Something similar is what happened with the Disney live-action-animation game changer, albeit in a different genre and atmosphere. The mystery surrounding a Hollywood superstar and a suspicious murder began life as a novel where all the plot elements were borrowed from the Noir genre, and then given a very surreal twist. Like the film, the story takes place in a world where fictional characters somehow have the ability to come to life. The book branches off into a very different path, however. It's one of those situations were the initial drafts of all characters are missing something vital.

Roger, for instance, turns out to be the actual villain of the piece. Others like Eddie, Jessica, and Herman are no better, and the mystery is lacking the sense of intrigue and momentous import that it does in the film. Hell, Christopher Lloyd's character doesn't even have a real counterpart unless you count an evil genie as the original draft version. So yeah, it's not the sort of book that would work as a movie. That's why Spielberg, Zemeckis, and animator Richard Williams all decided it was best to rewrite the whole story from scratch. To call this a good idea is a bit like saying you need to stay hydrated just to survive. It's pretty much unthinkable now for the story to exist in any other way. That's because it's like I said. What the filmmakers had on their hands in both cases was an incomplete story that they were able to finish in a successful, even downright iconic way. I'd have to cite flicks like this as the best case scenario for what can happen when turning a book into a film. It's the rare yet genuine pleasure that comes from knowing that you were able to allow the adaptation to triumph over the source material because you were able to tell the original story to its fullest artistic potential. It's perhaps one of the greatest secret rules of storytelling, yet there's never going to be anything hard and fast about it.

At the same time, there are plenty of cases where the exact opposite approach is true. These are the moments where the best course of action is to try and stick as close as possible to the source material. The best examples of this sort of approach are works like Rosemary's Baby, To Kill a Mockingbird, and The Graduate. It begs the question of where does a film like The Monkey fall in between these two poles? The first aspect of this film that jumps out at you is it's tone. It's director, Osgood Perkins, has made the deliberate choice to frame the and produce the entire story in the shape and form of a comedy. This is something the viewer can figure out for themselves with just a glance at the film's trailer. What we're treated to there is nothing less than a series of grotesque sight gags where it's clear the dramatic impact is meant to be taken with tongue well in cheek. It's where the audience is treated to such amusing sights as a hibachi stunt gone hilariously wrong, a motel patron diving headfirst into a pool charged with an electrical current, a camper turned into ground puree by a stampede of wild horses straight out of nowhere, and to top it all off, a priest giving the benediction of "Ho-lee-fuck!".

All of these incidents are filmed and framed as moments of black comedy. This is an establishing tone that Perkins carries over into the final product, and the viewer has to make up their mind on whether this particular choice of tone and approach works or not. To be fair, the idea of turning this story into a Horror Comedy does carry at least the sense of potential intrigue to it. The reason I'm able to say that is I get the sense this is the kind of story that can be open to several types of dramatic interpretation. The whole thing got started as a magazine short story somewhere back in the mid to late 70s, or early 80s. It's basic contents are so simple it almost qualifies as a modern day fairy tale. What King has given his readers is a riff on one of the oldest tropes in the Horror story's arsenal. Namely, that of the possessed, or demonic toy. He's not the first one to try his hand at this idea, by any means. I'm not even sure the honor goes to Rod Serling with The Twilight Zone episode, Living Doll. Though his is the effort most folks will point to when trying to track down anything like an origin point. Neither of them count as the most famous example. That honor goes to Brad Dourif's Child's Play franchise, which has pretty much cornered the market to the point that it's Chucky we all think about when it comes to the idea.

If we take the Dourif films as a baseline for comparison, then it's important to pay attention to the inherently wild tone those pictures set for themselves. Even the original Child's Play is a film that's aiming for this hybrid blend of the amusing and the horrific. That's because director Tom Holland seems to have had an awareness of the innate ridiculous qualities of such a premise. It's what allowed him the confidence to at least see if he could explore what it was like to tread that fine line between Humor and Terror. So with all these examples to choose from, it makes sense that Perkins would have a number of ways in which he could tell his adaptation. For instance, in it's original source text, King decided to play everything in a straight-forward manner, choosing to focus on the fear factor of the idea to the exclusion of any humorous elements the premise might carry along with it as well. Whether or not such ingredients are even there to be had, it's the road Perkins took when turning the short story into a film. The question then becomes how well did he manage to pull it off? How is an adaptation like this suppose to work? Are we supposed to find some happy medium between Humor and Horror? Or should fear be jettisoned in favor of a full-on, slapstick comedy of Gothic errors and happenstance?

The fair and honest is that I can see how this sort of picture can go either way. We seem to be dealing with one of those source materials that are able to contain a certain dramatic open-endedness to them. There's a multi-valence of atmosphere to a work like "The Monkey" which can allow it a greater amount of room to breath in terms of how the adaptor might want to stage it. This is the kind of story that, if done right, can succeed in a number of styles, whether comedic, straight-up Horror, or even a winning blend of the two. So from this perspective, there's nothing inherently wrong with the initial creative choice that Perkins uses to frame his adaptation. From the very opening scene, where Hal's disappeared dad (Adam Scott) takes the titular haunted artifact to a pawnshop, we can see that the director has chosen the Comedic side of things as the movie's primary tone. It means whatever idea that King's constant readers might have about the source material, they're going to have to expect this version to be a hell of a lot lighter, even in it's gorier moments (of which there are plenty). Like I said, an objective viewer will realize that this was a potential the original short story already came with.

It's not going to be any automatic dealbreaker if the filmmaker decides to let his adaptation be on the fun side of things. In fact, this is the kind of picture where, if done right, then it is just possible to create a new and fun cult classic. An ideal version of this would be for the film to have this edgy, yet enjoyable tongue-in-cheek quality to it. A good example of what I'm talking about is found in a movie like Joe Dante's Gremlins. There's just one good idea of how the tone for this adaptation can go. Let it have scenes that are basically setups and punchlines to a lot of fun Gothic jokes in between more dramatic and even heartfelt scenes. When it comes to the actual finished product, it looks for a moment there as if Perkins is going to give the audience at least something in that kind of Humorous Horror vein. The trouble is this turns out to be one of those film versions that can never quite get the right handle of its source material. What Perkins has done here is to take all the likeable three-dimensional characters from the short story, and turned them into these walking-talking mannequins that go around spouting unfunny jokes in a credulous, disaffected slacker-dude-bro manner that doesn't land well. It just gives the idea that everyone working on the film is operating on a kind of autopilot all the time.

This sense of disaffected disengagement, coupled with a lot of unnecessary plot complications is what tanks the film when the final reel is over. King's original idea was one of those so simple a child could understand it premises. Main character stumbles upon demonic toy. Demonic toy begins to wreak havoc. Main character understand the gravity of the situation, and tries to get rid of demonic toy. Main character thinks he's succeeded, only for the toy to pop back up again in his life, like a demented jack in the box. Demonic toy goes on yet another killing spree. Main character manages to finish demonic toy off once and for all. Happily ever after, and the fairy tale is complete. This kind of story doesn't need the sort of complications that Perkins sees fit to toss into the mix. The director takes the basic template of King's story and tries to spin this tale of dangerous sibling rivalry out of it. In this version, Hal and Bill (both played by Theo James) are setup as hero and villain of the piece, respectively. In effect, the character of Bill is revealed as the story's ultimate true villain. What happens in Perkins' version is that after they discover the Monkey, the Shelburn boys cause a number of deadly accidents by futzing with the gosh damn thing, and it doesn't take long for Hal to decide to bury the object where no one can ever find it. They toss the toy into a deep well located somewhere at the end of town, and Hal tries to put it all behind him. Bill, meanwhile, goes back later on and retrieves the Chimp as his personal hit man.

In other words, for whatever reason, Perkins has chosen to let Hal's brother be the true ultimate villain in the adaptation. He's revealed as having kept the Monkey in secret, and that he uses it to exact all sorts of gruesome revenge plots against the citizens of the small Maine town where he now resides (because of course Maine is going to figure in a Stephen King Horror story). There are a number of self-defeating problems with the direction Perkins has decided to take things in. The secondary issue might be described as how it muddies the film's sense of threat. The audience is left confused over who is in charge as the main villain, and hence where the sense of Horror should be focused on throughout the picture. This lack of focus is often the kiss of death for any fright flick that can't make up it's mind on were it's source of Terror lies. It leaves the audience confused as to not only where our attention should be directed at the climax. There's the added complication of not knowing whether this means we're actually supposed to root for the freakin' demonic toy! I've heard there was this trend in Horror movies not long ago where filmmakers were curious to see if it was possible to humanize the villains of the genre. However, this curiosity seems to have run aground on the fact that sympathy is impossible.

There's no way you can make characters like Freddy, Jason, or Leatherface in any way identifiable. I can't tell you if Perkins was doing the same thing here, or not. I just know he muddles the picture by the time we get to the final act, so that the story as a whole gets harder to follow than it should be. It's not helped by the fact the director sees fit to pile on more sight gags to moments that should be devoted to further narrative clarification. At the same time, it's like if you even create the need to take time out to explain what's going in a story this simple, then it's a pretty clear sign that you've dropped the ball. That's just what Perkins has done in this film, and it leads to the judgment call on the film's ultimate fault. The director saw fit to complicate what should have remained nice and simple. This is the kind of story that's meant to function well as either a half-hour or feature length episode of The Twilight Zone, or a show like Tales from The Crypt. There's no need to go beyond these obvious boundaries with a source material like this. It should be in-and-out with as little fuss or muss as necessary. Instead, Perkins gets stuck on trying to work out a theme that turns out to carry a very personal level for him.

In fact, the more you understand the reason why the director let the film get so complicated, the easier it is to understand why the final product is so messy and confused. To understand this part, you're going to need to hear a bit of backstory. Oz Perkins is the son of Anthony Perkins. In other words, he's the child of Norman Bates. In interviews on this adaptation, Oz has made it clear that working on a film like The Monkey has been a form of therapy for him. It's his way of trying to deal with the sudden and tragic deaths of both his parents. It makes for a very uncomfortable subtext to the picture as a whole, and what's kind of sad about it is that I'll swear it's like you can tell the director is choosing to run away from or shirk the issue by tossing off a few platitudes about life and then covering up his obvious grief by introducing a wacky, three-stooges style sight gags. It doesn't make the film any better once you understand this. If anything, that just makes it worse. There's no way for me to find anything salvageable in all this. The picture remains a piping hot mess, yet it's possible to understand why that turned out to be the case. So while I can't give this a passing grade, I can cut the director some slack.

The trouble is that still leaves audiences with an ultimately abortive film version of one of Stephen King's best work. It leaves us with the question of how could a better adaptation of this story play out? Well, one idea I had was pretty simple, and it goes back to what I said a minute ago. The key thing about "The Monkey" is that it's basically an episode of your typical 1980s Sci-Fi/Horror anthology series. It's either a movie or an episode of Tales from the Darkside waiting to happen. I think the first thing any good adaptation should do is to lean into the aesthetic roots of the story. Give it the proper atmosphere that can tap into and suggest an idea of that kind of early to mid 80s zeitgeist. Let the film's imagery have this sort of faded, autumnal feel as seen through a nostalgic lens of amber. This is the sort of story that wants to be told in a way that is able to recapture a sense of the lost glories of 80s youth. It means that while the setting has this faded photograph album look to it, there should also be room leftover for this kind of warm vibe to everything. It should suggest to the audience the notion of the sun setting on one last great moment of Summer, with just the proper hints of Fall on the horizon.

In terms of what kind of setting this ideal version would be like, then really, all you have to do is set the action in the prototypical suburban setting of films like E.T., Back to the Future, or The Burbs. It should be the sort of place where you can still see bunches of kids riding their bikes on their way to having an adventure, even if it's just for an outing of fun at the ballpark or the local videogame arcade. The neighborhoods and streets of this version should be a blend of the bucolic picture postcard and the menacing. On the one hand, most of the houses, shops, and business establishments should give off this sense of homespun vibrancy. Once the action takes us further away from the welcoming embrace of the Spielbergian enclave, then the buildings should become more scare and rundown, with weeds and tall grass starting to reclaim the stage setting. What few buildings there are in this other aspect of the plot should be old brownstones that look ready the cave in on themselves, or else have that familiar burnt out look. Whatever few cars you see along this route are junked out and abandoned. This other setting should suggest the sense of a place that people use only in order to forget about things. It should be empty, sad, and lonely, with the proper hint of menace lurking just out of sight in the shadows. It should be the kind of place where you don't want linger around once it gets way past sunset time.

This kind of setup helps to create the perfect sense of a light/dark contrast that the story can work with and play off of as its main narrative action unfolds. The protagonist should find his struggles with the haunted toy forcing him onto a tightrope between these two poles. Hal's quest to destroy the Monkey once and for all should therefore be about him wanting to hold on to the light and promise signified by that Spielbergian - John Hughes style of life that he might be able to build up for himself, and the darker aspects of his existence represented by the rundown neighborhood that the toy keeps edging him towards with each fatal clash of it's cymbals. Perhaps the final confrontation between Hal and the Monkey will have to take place in a location within this darker setting. Whatever the case, the crucial point comes in how you choose to handle the Horrors of this story. King's methodology in the original short story might be described as the classical Bradbury method of approach. He tends to play up the drama by highlighting the sense of existential dread that the Monkey symbolizes. The writer seems to be aiming at this idea of the demonic toy as a metaphor for what was described by thinkers of the Renaissance period as Infortuna, or Misfortune. In that sense, King's story bears a striking fellowship with Jordon Peele's Nope. At one point in the latter film, a character ponders the idea of a bad miracle.

It's this idea that a freak occurrence can strike at any moment, and that such events might in themselves be an ill omen, or harbinger of worse things to come. King and Peele have a surprising amount of fun playing around with what is ostensibly a pretty morbid concept. They take the strange logic of the notion as far as they can go with it. Tracing the concept to its highest point leaves both writer and director asking their shared audience if the possibility of the bad "miracle" can have a sense of supernatural malice behind it, and how far would such an ill will be willing to go if terms of "amusing" itself? Another way to describe the concept King is working with is to call it a sense of Bad Fate. This is something of a recurring theme in all of the writer's fiction. King seems perennially obsessed with the question of fate versus free will, and how much control we humans have over our lives. In "The Monkey" this question centers around Hal Shelburn's attempts to destroy an evil artifact which has been responsible for a lot of the setbacks in his life. This is a fictional conceit with a lot of interesting thematic meaning behind it, and this seems to be the reason why short story has hung around so long. There's a lot of what Tolkien described as Applicability to be had in a creative concept like that.

I get the sense that Perkins was trying to grapple with this notion in his adaptation, yet he just couldn't get the proper handle on it for reasons personal as well as professional. In terms of how others might work with this theme, then there's no reason not to keep the tongue and cheek dark humor approach to the story. What I would suggest, however, is that the adaptor avoid the mistake that Perkins makes. He ultimately couldn't decide and settle on how serious or silly everything should be, and the film kind of has no choice except to suffer for this crucial lack of creative insight. My own suggestion for how to avoid these pitfalls brings me to my final suggestion for a better film version. If you want to inject humor into the proceedings of King's narrative (and I can see the logic of such a choice, considering how heavy a theme he's working with) then it needs to be directed by someone who has has a good, almost instinctive grasp of that fine line where good Humor and Horror mix well together in a crowd-pleasing way. It's with this provision in mind that I can't helping thinking that the director best suited for a project like this would have to be the filmmaker who gave us Gremlins, Joe Dante himself.

All his life, the man has always had this knack for finding the best possible middle ground between light-hearted family Fantasy adventures and dark subject matter. The tale of Misrule that envelopes Kingston Falls is just the most memorable example of his skill in this direction. Something tells me if you want an adaptation of "The Monkey" to be any kind of success, then you sort of have to make it in the same vein as Dante's best work. Like with the story of what happens to the Peltzer family when they get a new "pet", the story of the Shelburn clan and their run-in with a bad miracle maker should be told in the same vein. The adaptation needs to find the right happy medium in order to succeed. It's got to find the best (not the right) way of straddling the fine line between laughter and fright. I'd argue it's possible to keep at least some of the dark humor that categorizes Perkins' approach, while at the same time I get the sense not that it needs to be toned down, so much as given a better channel or outlet of expression than what this adaptation is able to do. In the best Dante tradition, what a better version of The Monkey should be like is a live-action Looney Tunes flick. It's Dante's trademark style of filming.

The director has made no secret that perhaps the greatest influence on his work are the films of Chuck Jones. It's rare for viewers to pick up any one of his films and not catch either a passing reference, or an entire sequence devoted to the classic Warner Bros. Animated Stars. Dante has crafted an entire career that is haunted by the shades of Bugs and Daffy. He's also made no secret that the Warner cartoon style is something he makes an effort to incorporate in all of his films. The fact that this element can be found in all of his best works (those that will be able to stand the test of time) points to a surprising achievement on the director's part. He's got to be the single filmmaker I know who has found a way to turn the Looney Tunes formula into a successful live-action format. It's just one of those aesthetic skills that are so apparent that you don't even notice it without giving the topic a lot of close thought. Once you do see it, however, it's like everything falls into place, and the true skill of the artist becomes recognizable for the first time. It's what allows me to say that a King story told in the blended Jonesian style of Dante's artistry would be just the right sort of combo and creative vision for The Monkey.

In terms of how such a story could be told, then there are precisely two ways I'm aware of. The first has already been outlined well enough. All you'd have to do is to meld the elements of Spielberg and Jones with that of King to create a nostalgic throwback to the Horror and Fantasy films of the 1980s. The other one is to go with another form of homage. It's just possible to see King's short story filmed in such a way as to make it a tribute to the schlocky, Drive-In B Movies that were a major influence on both the director of Gremlins, and the author of "The Monkey". King has made no secret of his admiration for the kind of films that were regularly mocked on MST3K. Dante is one of those artists who feels very much the same way. This counts as the second major element in the director' repertoire. It's his love for all of the best cheese offered by the Sci-Fi and Horror films of the 50s and 60s, a lot of it from the hands of Dante's own mentor, Roger Corman. It's very easy for me to see The Burbs auteur creating a version of The Monkey as this black and white tribute to Corman's cinema. The only trouble with such and approach is that even if it's successful, it would still be too niche to succeed. Therefore the obvious choice is to go with the same vibe as that found a film like the original 1984 Gremlins.

That's why I'd support the effort to have Dante take another shot making The Monkey come to life. It would be a fun return to form for the great 80s legend. It's the sort of thing that, if done right, could function in one of two ways. We're talking either a late career revival here, or one last final grand bow from one of the most influential filmmakers of his generation. I'm comfortable with either course. I'm also pretty certain that this is perhaps the best we can ever get out of a story like "The Monkey". We're talking about on of those fright tales that amounts to a children's bedtime story blended with a 50s Drive-In B Movie that's presented as one of those cheesy yet somehow forever endearing episodes of an old, obscure, 80s Horror Anthology show. That's the kind of aesthetic you should aim for with a story like The Monkey. Osgood Perkins wasn't able to achieve this vision with his own adaptation. The good news is there's still time for a better version if anyone really wants it. I know I'd look forward to it.

No comments:

Post a Comment